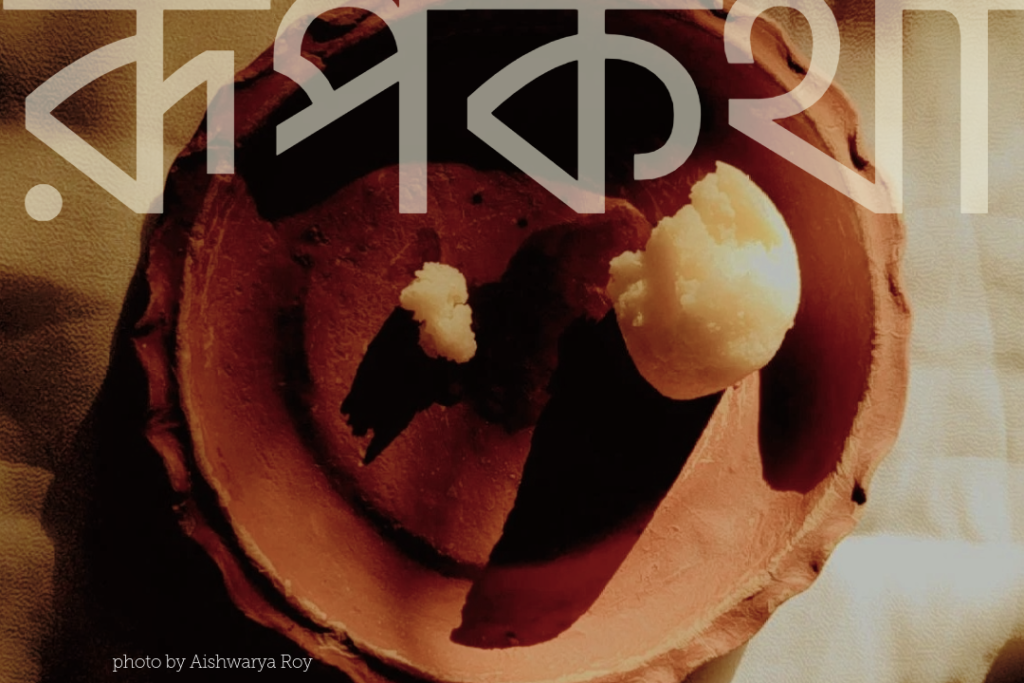

Whether for the love of the story, or because of a colonial hangover we have yet to calm, children often grow up on fairytales that end with glass slippers and golden crowns. But my childhood was made of রূপকথা (rupkotha), where snakes spoke in riddles, rivers turned into mothers, and girls outwitted kings.

My parents read to me in Bengali.

Not just bedtime tales, but entire worlds.

They handed me a language that smelled of mustard oil, sounded like rain on a tin roof, and knew how to say both ‘I missed you’ and ‘don’t do that again’ in the same sentence.

But outside home, in the corridors of my English-medium school, knowing my own tongue too well became a mark of shame. In school I once recited a full poem by Sukumar Ray in 6th standard without missing a beat, and after class, a girl asked me if I was “from a Bengali-medium school”. Not out of curiosity, but like it was something I ought to apologise for.

So I learned early: That my rupkotha wasn’t welcome.

That my vowels were too round, too soft, too Bengali.

That to be taken seriously, I had to forget the lullaby rhythm of my tongue, and start

speaking in the clipped, neutral syllables of belonging.

That’s when translation began for me, not as a skill, but as a survival tactic. Not to understand, but to be understood.

And I watched it happen all around me. Friends who stopped calling their mothers Maa and switched to “mom”. Sons who laughed at their fathers’ thick accents. Girls who winced at their own names if the teacher pronounced them in a tongue too native to swallow.

We were never told to erase ourselves — but many of us did it, anyway.

I think about this every time someone from Bengal hesitates to speak in Bengali. At cafés, at airports, at open mics, even at home sometimes, where English has grown like mold over the walls of our mother tongue.

Yes, we translate to be understood.

But how do you really translate অভিমান) (obhimaan)?

That tender, bruised sulking that isn’t quite anger, but feels heavier than rage?

How do you explain মায়া (maaya)?

That love which is more attachment than affection, more ache than warmth?

I know people who would rather fumble in French than speak Bengali in public.

Who apologise for their mother’s accent.

Who translate Tagore in their captions but roll their eyes at রবীন্দ্রসঙ্গীত (Robindra Shongeet)

And then wonder — how did we become more afraid of getting it wrong than of forgetting it altogether?

But some days, even amidst that erosion, I see subtle sparks of resistance.

Flickers of memory that refuse to dim.

In a friend who teaches her child দুঃখ (dukkho) before “sad”.

In the way my Baba still writes grocery lists in Bengali script.

In the mustard oil bottle that Maa never replaces with olive oil, no matter what the diet blogs say.

Because so much of our lives isn’t one language or the other.

It is the way সর্ষে বাটা (shorshe baata) burns and heals at the same time.

It is the memory of our Thammi opening a pomegranate for us, letting the seeds scatter like stars across the sky of our plate. It is in the শুক্তো (shukto) that always tastes like something sweet and creamy, even though it contains bitter gourds. In কচুর লতি (kochur loti) that we never learned to explain, only crave.

Because this, too, is survival.

We are still here — not because we adapted, but because we remembered.

And yes, I’m writing this in English.

Because I want you to understand me.

Because maybe this is the only way you’ll listen,

and the irony will remain undefeated.

But also — because I want you to feel what it means to carry a language in your mouth like a prayer you were told to outgrow. To love a word so much that even when you say it in translation, it still tastes like home.

.

.

.

.

.

*** Translations:

Rupkotha: Bengali fairy tales

Robindra Shongeet: Songs written by Robindranath Thakur (Tagore)

Shorshe baata: Mustard paste

Thammi: Grandmother

Shukto: A traditional culinary dish from Bengal, with bitter gourd as a key ingredient

Kochur loti: Taro stolons