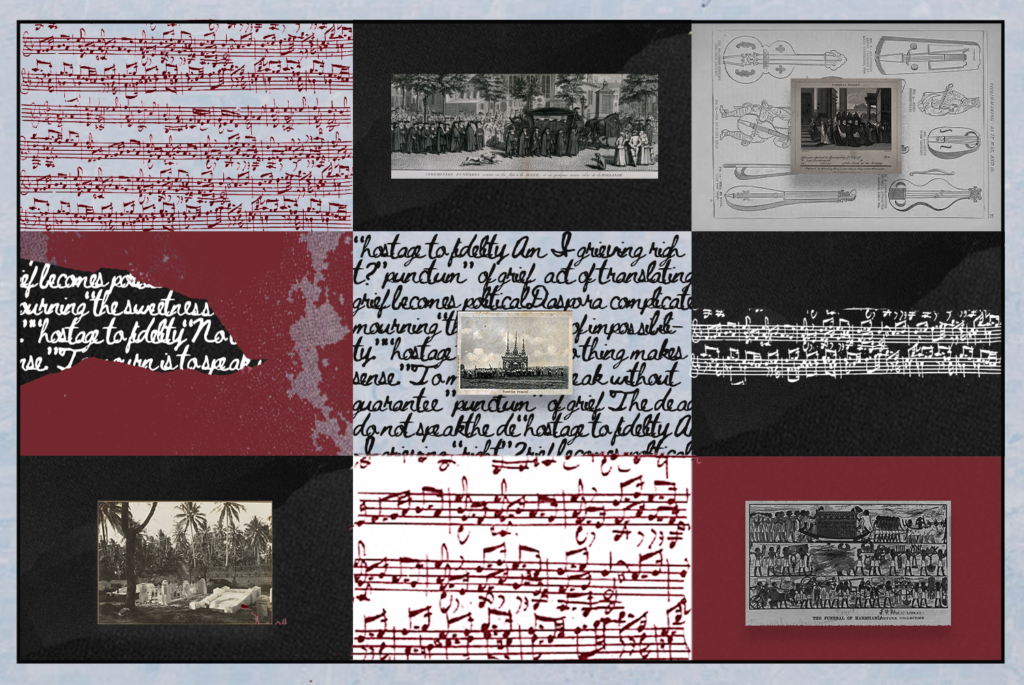

There is a story—part musicology, part myth—that Johann Sebastian Bach wrote the Chaconne, the monumental final movement of his Partita No. 2 in D minor for solo violin, after returning from a journey to find his wife dead, and already buried. In this telling, Bach’s Chaconne is not only a composition, it is an act of mourning. A grief too large for words, translated into sound.

In fact, that is how I discovered this particular piece, in the terra incognita of my own grief, I turned to art to be my instrument of cartography. Music became a map for what I could not name, an instrument for my silences. And in Bach’s Chaconne, I found not consolation, but a mirror: a way to stay with the pain without resolving it, a loop I could walk through and still remain lost.

Violinist Yehudi Menuhin once said the Chaconne is “the greatest structure for solo violin that exists.” For Joshua Bell, it is “one of the greatest achievements of any man in history.” But perhaps it is not greatness we should hear in it, but translation of sorrow, love, bewilderment. There are no lyrics, no dedications. Only pattern and repetition. The same phrases echo, shift, modulate; just like a mourner, retelling the story of a loss, hoping to hold something in place, knowing they never will.

To grieve is to translate absence. It is to become, as Jacques Derrida once said of translation itself, a “hostage to fidelity”, bound to the impossibility of recovering the original, and still compelled to try.

The Work of Mourning and the Inadequacy of Language

Derrida, writing in The Work of Mourning (2001), often described mourning as a simultaneous responsibility and impossibility. One must speak of the other, but without possessing them. Mourning is not about replacing the lost; it is about carrying them forward in language, in gesture, in silence. Grief, then, is a translation without an original. We do not translate from a stable source. The dead do not speak. What we translate is a void, an impression, a touch that has vanished. He asks: “Can one be responsible for someone else’s memory?” The mourner answers through the act of telling and re-telling through rituals, stories, even the pauses between words.

As Roland Barthes suggests in his 1978 lecture series The Preparation of the Novel, every act of writing, and by extension, translation, is marked by an inherent exposure to failure, a ‘snag’ in meaning that reveals the impossibility of complete transmission. In this view, translation is not merely a bridge between languages but a site where meaning is perpetually deferred, unsettled, and remade.

In Mourning Diary (2010), the fragmented, shattered notes Barthes wrote after the death of his mother, he confesses: “The impossibility of writing. It is perhaps the most profound expression of mourning.” And yet, he writes. In broken time, in half-thoughts, in a diary that is less a record than a wound. He does not attempt a full narrative of loss. He does not synthesize. His mourning is recursive, contradictory, granular.

To read his book is to witness the “punctum” of grief – a wound that pierces the subject, irrationally and intimately. It is not the event of death that breaks him, but the traces: the light left on in her room, her toothbrush, her handwriting. Grief is never clean. It leaks. It interrupts.

To write from it is to translate that leak into form, while knowing the vessel will never hold.

Care as a Grammatology of Grief

Where Derrida and Barthes speak to grief as philosophical and semiotic unraveling, feminist philosopher Eva Kittay brings us to its most intimate terrain: care.

In Love’s Labor (1999), Kittay argues that dependency is not an exception to the human condition, it is its foundation. Grief exposes this with merciless clarity. When we grieve, we are not just mourning the loss of a person; we are mourning the collapse of a relationship, a structure of care. We are mourning how we were held, seen, relied upon; or how we held, saw, loved someone else.

Kittay insists that care work, often feminized, invisible, and devalued, is a form of translation: the conversion of emotional, bodily, and ethical need into action. Feeding a parent. Holding a child. Remembering a friend’s voice when no one else does. These are acts of translation. They turn the unspeakable into touch, gesture, memory. They are ways of keeping the absent alive, beyond metaphor, in routine.

When the one we cared for is gone, or when the one who cared for us is gone, the world stops making sense in the way it once did. Grief emerges as a rupture in the logic of dependency, a tear in the web of obligation and love that made the world inhabitable.

To translate this grief is to try to build new grammars of care, to reconstruct how to live in a world where the relational syntax has fallen apart.

Ritual, Repetition, and the Limits of Fidelity

Like translation, mourning is haunted by questions of fidelity. Am I grieving “right”? Am I remembering too little, or too much? Is this how they would want to be recalled?

Rituals of mourning like funerals, prayer meetings, community gatherings of friends, are translation devices. They do not bring back the dead. They organize the chaos. They create a rhythm when time feels disjointed. They allow the living to return, again and again, to what is no longer there. But rituals also reveal the social hierarchies embedded in grief. Whose loss is recognized? Whose death receives ceremony, obituary, elegy? Feminist and anti-caste thinkers remind us that not all grief is public. Not all grief is grievable.

In this way, the act of translating grief becomes political. To insist on mourning someone who has been erased by the state, by caste violence, by gendered neglect, is to demand visibility. It is to say: they mattered. I will carry their trace into language, even if no one listens.

The Personal Archive: Translation as Re-memory

Grieving often turns us into archivists.

We become translators of the self, shuffling through text messages, voicemails, clothes, photographs. Each object becomes a sentence we try to decode: what did this mean to them? What does it now mean to me? But unlike formal archives, grief’s archive is fragile, haunted by gaps. We misremember. We forget birthdays. We invent conversations that never happened just to hear their voice again. And yet we keep returning. We narrate them into being.

In this sense, grieving becomes an act of ‘re-memory’,a term used by Toni Morrison to describe not just the retrieval of the past, but its reconstitution through love and will. We do not recover the dead. We invent forms that allow us to live with their absence. A playlist. A recipe. A new name for a child.

These are not translations of “truth” alone, they are also translations of longing.

Grieving in Translation: A Language Without End

What happens when we try to grieve across languages?

Diaspora complicates mourning. So does exile, political displacement, religious erasure, generational silence. The language in which you once loved someone may no longer live in your mouth. Your mother tongue may not be your mourning tongue. You may carry memories in your mother tongue and have no words to translate them into English. You may write elegies that can only be spoken to yourself.

The act of grieving, then, becomes not only relational but linguistically dislocated. You carry the burden of remembering across fractured tongues, translating your pain for an audience that may never fully understand. In this process, something is always lost. But something else may also emerge: a mourning accent, a hybrid language of gesture, silence, and fugitive memory.

In such moments, grief becomes a translation between selves, between the person you were with the one you lost, and the person you must become without them. The work of grief is not only to remember, but to re-home memory in a world that has moved on, or never recognized the loss to begin with.

Think of the grandmother who sings lullabies no one else understands, the migrant father who lights a candle in secret, the queer lover who cannot name their partner in obituary columns. These are not acts of closure. These are translations of survival that may be halting, incomplete, but deeply resistant. You don’t say I miss you in every language. Sometimes you light a lamp. Sometimes you cook their favorite meal. Sometimes you cry into your pillow using the cadence of another country.

This is grief’s final lesson: translation is not resolution. It is a practice. A circle. A pulse. The act of returning to what cannot be said, and trying again anyway. It is what Roland Barthes calls “the sweetness of impossibility.”

Repetition and Recursion

Translation is often imagined as movement from one place to another, one language to another, one self to another. But what if it is less about movement and more about recursion? What if, in grief, translation becomes a form of circling, spiraling inward, returning again and again to the wound, the moment, the name?

Grief does not follow a linear trajectory. It returns in strange rhythms: the third week, the first anniversary, a song in the supermarket, the smell of an old t-shirt. Each recurrence reopens the question: what was lost, and how can I hold it now? In this sense, grieving is not about moving on, but about moving with, carrying the past as a companion, not a burden. This is where translation and grief meet most intimately: in the acceptance of incompleteness. We know we will never find the right word. We know we will never rebuild what was lost. But we continue the act of trying not only to recover, but to also remain in relation.

In Eva Kittay’s language of care, this is what dependency demands: not perfection, but presence. To translate grief is to stay present to the mess, the asymmetry, the awkwardness of not knowing what to say. It is to be with the other (or their memory) in a form that never arrives fully, but arrives enough. Repetition becomes a form of holding. A ritual. A reconstitution of what cannot be possessed. Barthes writes the same entries over and over: “I miss her.” “Nothing makes sense.” He knows these words do not suffice. But their repetition becomes a rhythm of survival. Each time he writes, he keeps his mother alive in sound.

This recursive grief is not regressive. It is a kind of fidelity to feeling. To echo the beloved, even imperfectly. To mistranslate, and in doing so, make them live again.

The Incomplete Sentence

Roland Barthes never completed his memoir of mourning, his fragments remain scattered. Jacques Derrida kept returning to his friends’ deaths in multiple essays, unable to close the door. Even Bach, who wrote the Chaconne as a vast and layered lament, does not resolve it triumphantly. The piece ends as it began, with an unresolved cadence, an echo.

Perhaps this is what we owe the dead: not closure, but continuance. A refusal to make their absence tidy. A willingness to live in the sentence that never ends.

As feminist thinkers remind us, especially in contexts of structural violence, caste atrocity, and state silence, grieving is political. It refuses to let the disappeared be forgotten. It keeps the story open. It keeps the wound visible. The incomplete sentence says: they mattered. I will keep speaking, even if I get it wrong. Even if no one listens.

In grief, we are always translating ourselves, our dead, our losses, our love. We reach across absences with imperfect tools, inventing forms that can carry the weight. Letters, diaries, resistance songs, recipes, photographs, memorials, silence. These are all languages of grief.

To mourn is to speak without guarantee. And sometimes, even the failed translation that is offered with care, repeated with love, is enough. And sometimes, even silence is the most faithful translation of all.

.

.

.

.

.

References:

- Barthes, R. (2010). Mourning Diary. Hill and Wang.

- Barthes, R. (2011). The preparation of the novel: Lecture courses and seminars at the Collège de France (1978–1979 and 1979–1980) (K. Briggs, Trans.; N. Winch, Ed.). Columbia University Press.

- Derrida, J. (2001). The Work of Mourning. University of Chicago Press.

- Kittay, E. F. (1999). Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality, and Dependency. Routledge.

- OnBeing. (n.d.). The Story Behind Bach’s Monumental Chaconne. Retrieved from https://onbeing.org/blog/the-story-behind-bachs-monumental-chaconne

.

.

.

Original artwork by Nahal Sheikh: nahalstudio.org