For an audio-visual project on outward migration from Bihar, I was speaking to professor Brahma Prakash, a writer and Professor at JNU, over a Zoom meeting. He said, “…Britishers took people from working class-caste/Dalit-Bahujans, as labourers to their plantation fields in Caribbeans. They knew that Brahmins and other upper castes were not generationally trained for such kind of labour…”

The upper castes (non Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi), especially Brahmins, traditionally posed as an intellectual elite and through the privileges of the Caste System, were exempted from manual labour. Such division of labour which was held intact by the caste-based segregation of work and labour persists until today. The Mandal Commission Report revealed that upper castes, particularly Brahmins, occupied a disproportionate share of influential bureaucratic and institutional positions in India, despite the country’s efforts to promote social justice through affirmative action. The Commission found that Brahmins, along with other upper-caste groups, dominated key roles in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), Indian Police Service (IPS), and Indian Foreign Service (IFS), as well as in other prestigious government jobs. In contrast, the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs), who constituted a substantial portion of India’s population, were significantly underrepresented in these positions. The Commission estimated that OBCs comprised about 52% of the population, yet their representation in government services, especially at higher levels, was far lower. This disparity was a key driver behind the Commission’s recommendation for 27% reservation for OBCs in government jobs and educational institutions, along with increased reservations for SCs and STs.

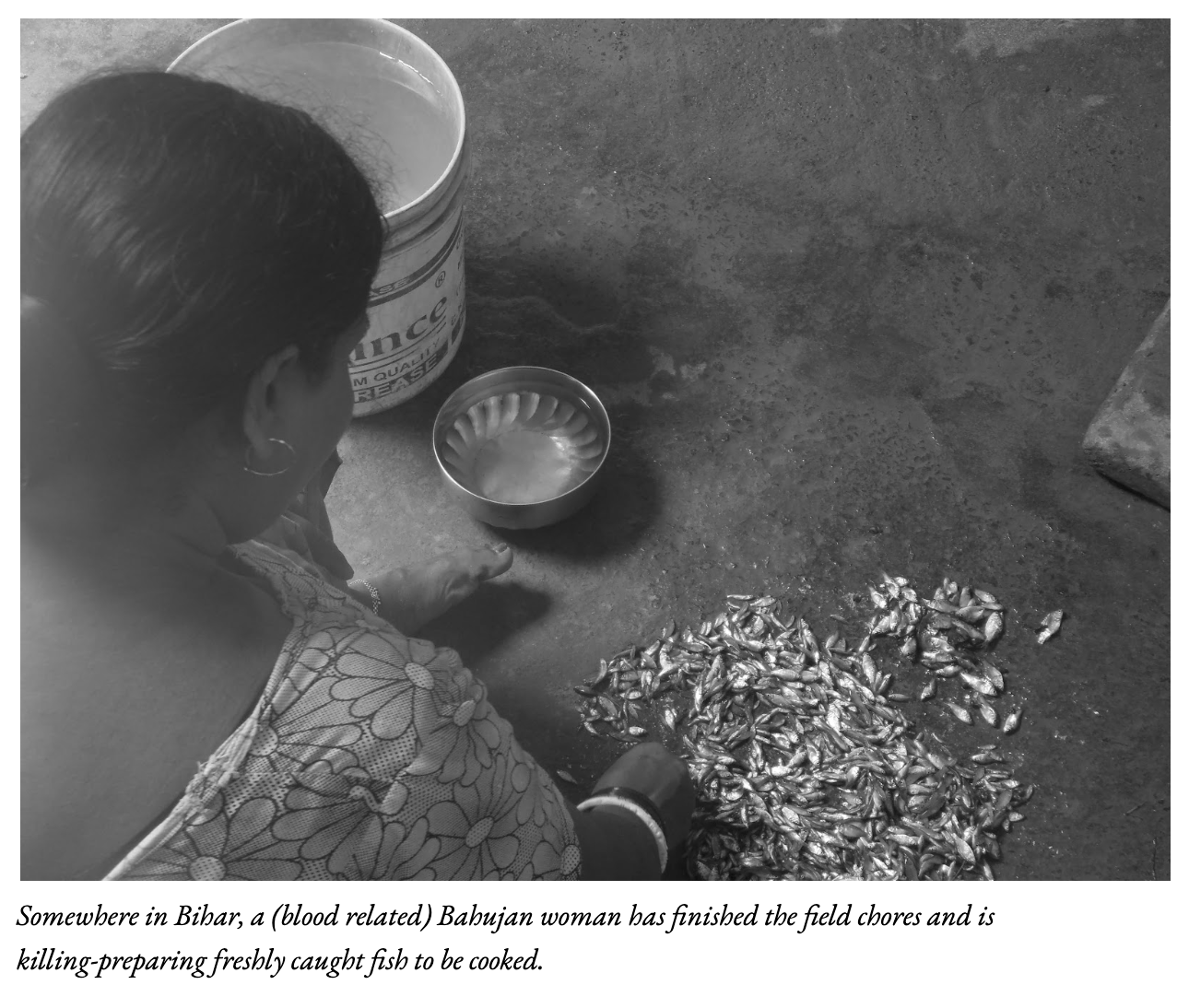

I cannot help but think of labour that consumes the bodies of Bahujan (here, OBC) women of my kin. Women with mud stained hairy legs, cracked and hardened feet, palms carrying scars from the cut of a sickle, singing ropani** in the paddy fields. Women of all ages get up before the sun climbs the sky, put fire into the chulhas, feed the cattle, bundle up the grass–and work on a never ending list of other chores.

In many Bihari Dalit-Bahujan-Adivadi (DBA) households, the husbands are rarely home and the women are named ‘left-behind wives’ in the academic glossary. Managing the household without a companion’s support increases the labour, both physical and emotional for them. While the data suggests that men who migrated were able to help their families financially, the life of the migrant man in cities has not been easy, and the life of the left-behind wife is often filled with the pain of losing the proximity with her companion to basic material needs of the household.

The emotional toll on the woman extends beyond loneliness. They bear the responsibility of raising children, handling finances, and navigating complex social(caste based and gendered) structures often stacked against them. The absence of a ‘male figure’ in the home can make them more vulnerable to social scrutiny. It is even tougher for a ‘left-behind wife’ with any form of disabilities. Sometimes, the amount of money the migrant husband sends is insufficient and they have to work as field laborers in the native village, either on their own lands(as marginal farmers) or on others. Despite these challenges, many of these women display remarkable resilience, forming support networks with other left-behind wives, and actively engaging in exchange of knowledge vis-a-vis: lived experiences, wisdom, cues-and-tricks which help them sustain their families in the absence of their partners.

The misogyny that exists within the household, often increases the burden for the women in addition to caste based gendered forms of labour. The Bhojpuri folk songs from Bihar reflect the pain of the left-behind wife as accompanied with the push-pull within the family dynamics. Asha singh writes about one of the songs where a left-behind wife complains about being kept deprived by the in-laws of her migrant husband–

“Toharo je maiya prabhu ho awari chhinariya ho

Tauli naapiye telwa dihalan ho ram

Toharo bahiniya prabhu ho awari chhinariya ho

Loiye ganiye hathwa ke dihalan ho ram”.

(Oh husband, your mother is such a bitch,

She gives me only a few drops of oil.

Oh husband, your sister is such a bitch,

She gives me limited flour to cook.)

–

As per the Caste census of my home-state, Bihar, the ‘General Caste’(non DBA) population stands at 15.5224%, 27.13% Other Backward Class; 36% Extremely Backward Class, 19.65% Scheduled Caste, 1.68% are Scheduled Tribe. The data on poverty percentage tells there are 25.09% poor families in the ‘General Category’(non-DBA), 33.16% poor families in the Other Backward Classes (OBC); 33.58% poor families in the Extremely Backward Classes (EBC); 42.93% poor families in the Scheduled Castes (SC); and 42.7% poor families in the Scheduled Tribes (ST). This is evidence of the broader relation between class and caste. An important part is played by one’s social identities in constructing one’s materialistic capacities and labour that one’s body is subjected to. To explain the hierarchy that exists in relation to labour and bodies of the labourers’, BabaSaheb’s argument stands as–

“Caste System is division of labour as well as division of labourers…The Caste System is not merely a division of labourers which is quite different from division of labour—it is a hierarchy in which the divisions of labourers are graded one above the others.”

An International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) study noted that the caste and gender hierarchies work together to perpetuate the division and devaluation of certain kinds of work, “Gender and caste-based occupations such as the traditional midwife or dai, the female manual scavenger, the leather worker, all fall within this ambit. Much of this work is performed intergenerationally and is retained within the same gender, as young girls are prepared to take on work that their mothers do. It is a clear form of social reproduction where a segment of the society is pushed to enter informal labor of a specific kind.” Caste based gendered training of the girls from a young age is extensively discussed by the writer, academician and anti-caste activist Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd in his book ‘Why am I not a Hindu’. From girlhood to adulthood, women’s positioning in the caste system allows them no escape and rest, only toil and exhaustion –the two sets in dichotomous relation to each other. Caste based division of labour decides for the woman’s body the amount and kind of labour that it has to engage in. Hence, there is no possibility of a successful feminist movement without it being anti-caste.

–

While writing this essay, I also wondered about the question of ‘who is a woman?’ since there is no clear one answer to who and what is a ‘woman’. On one hand, the femininity of DBA women have been historically and socially posed as ‘not sufficient’ by the standards created by the privileges enjoyed by Savarna women in maintaining their cis-femininity. On the other hand, the trans***women from the DBA community lie on the intersectionality of layers of oppression, made worse due to the lack of basic rights like healthcare access, employment opportunities, strict laws to protect persistent violence against them, horizontal reservations etc. In a world so unequal, it becomes important to investigate labour as locatedness of Dalit-Bahujan-Adivadi women’s labour in context to welfare schemes of the country.

The migrant husbands of the left-behind wives can be found in rightful demands posed by Dr. Rahul Sonpimple who is many things and an Ambedkarite, sociology scholar and founder of AIISCA(All Indian Independent Scheduled Caste Association). Dr. Sompimple argues against the subjectivity centered reduction of Caste System to different realities as held by different people, holding that Caste is beyond one’s body and is the material reality that is reproduced. He investigates the caste identity of the bodies that build big metro cities and sustains them through their labour.

Over 92% of the eight crore informal sector workers registered on the e-Shram portal earn a monthly income of ₹10,000 or less. The analysis of social categories reveals that 72.58% of the registered workforce belongs to OBC, SC, ST population: 40.44% from Other Backward Classes (OBC), 23.76% from Scheduled Castes (SC), and 8.38% from Scheduled Tribes (ST). Dr. Sonpimple rightfully questions the failure of the welfare state to return back to the ones contributing to economic growth, “if the economy is more than 90% informal economy, then the question comes, who are the owners of this informal economy.”

As popular culture and cyber space is embracing with open arms #girlboss, girlboss aesthetics, and the career pursuits of a ‘girlboss’, I loiter outside of such affairs of ‘women empowerment’. Loitering, I think of some women I know through biological association, friendships, through the journalistic work that I do (recalling the recent interview I did of Nirmala Putul, a poet, women and adivasi rights activist, and Panchayat head of Kuruwa in Jharkhand) and the older women who are the literary/philosopher godmothers I never really had– bell hooks, Audre Lorde, Babytai Kamble among many others. I often joke, “I am no boss-girl, I am just a girl (only for my femme days, of course)”

bell hooks in an interview once said, “Liberal individualism that makes freedom be doing whatever you want to do, being able to dress however you want to dress and call it whatever you want to call it. And so that’s not threatening. So in many ways, you can think of that as a kind of facilitator for many women going into the mainstream dominant culture, how to make peace with something that we can’t change or that has not changed. “ Certainly the boss girls mocking the domestic workers in instagram reels want to feel empowered in their workplace, certainly the boss girl who has an ICC(Internal Complaints Committee) at her workplace will not talk to her domestic worker about LCC(Local Complaints Committee) or be bothered by the lack of one in her district–certainly the boss girl has laboured hard to make it through patriarchy! Does the boss girl contribute to brahmanical erasure of the labour of women in the informal sector?

I think of a recent interview I did with Ms. Gudiya, an activist and VP of Shehri Mahila Kamgar Union. She told m “jo gharelu kaam karne jaati hain aurtein, wo ghadi ki sui ki tarah chalti rehti hain, bahar jakar kaam, phir apne ghar par kaam, rest nahi hota uski life mein.” The women working outside are also laborers within the house, the gendered chores that they do often go unacknowledged. The intersectional-oppression seldom allows the impacted body any rest or leisure.

Does the feminist imagination of leisure and self-care accommodate the work to be done at the policy level in the country to allow the bodies of Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi women the rest they never have? For Dalit- Bahujan-Adivasi women does the notion of leisure as a tool of feminist resistance arrive like a distant, perhaps unattainable promise? Does the conception of leisure overlook the harsh realities of their labor, survival, struggles, and the persistent violence they face in their daily lives? Can the idea of leisure be actualised for them without all the legal, political, social and economic justice?

Not leisure/self-care but Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi women’s laboured-tired bodies establish a deep connection with anger—both as an emotion and as a driving force. This anger is rooted in personal as well as institutional experiences of oppression. The bodies of the women carry this anger, which, if contextually displayed, often leads to repercussions that disproportionately affect them. Sometimes it might invite guilt from the oppressor, but as Audre Lorde has pointed out this guilt is not a response to the expressed anger but a reflection about their own action or rather the lack of it. Anger of Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi women is an important source of progress and change. Here, change is not a fleeting moment of relief, a smile, or a temporary feeling of ease; neither is it easing of tension while dealing with the oppressor elites. Instead, change represents a radical transformation of the structural conditions that can underpin the lives of Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi women.

Ms. Gudiya’s mother works at private construction sites, she actively works at the grassroots with women to make them aware of their rights. However, Gudiya tells me that she often feels limited whenever a muslim domestic worker has to change her name to a Hindu one to find work, or when a domestic worker has to hold her pee because the girlboss won’t let her use the bathroom on the grounds of ‘hygiene’. She feels angered and demands for better policies to be in place for the women she works for and with. Ms. Gudiya is currently busy with organising National level meetings in New Delhi for women in informal economy, the concerned unions and their members, activists, to gather and collectively voice their demand for better policies.

–

“In the East, it is untouchability that foregrounds the form and content of humiliation”, Gopal Guru further points out that the so-called modern social elites tend to reproduce structures, both institutional and social, that underline and renew the phenomena of humiliation. The first or second generation learners (specially women and queers) from Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi communities who manage to reach the universities of the metropolitan cities are perceived uninvited to the party– horrors of Manu are replaced by horrors of mythical ‘merit’. Their bodies inherit a complex relationship with labour and leisure from their mothers. The mobility that they aspire to gain through education, the rest that they aspire for their bodies is often denied by the making of the past and present of the institution(s) that they are a part of.

The topophobia associated with university campuses where upper caste feminists had once saturated the air quality index with anti-Mandal Commission slogans of “Reservation hatao desh bachao. “ has to find a place in one’s chest and the body. For the rest that is deserved by the bodies of Dalit-Bahujan-Adivadi women, we believe in Begampura, we sing what Raidas sang–

“…That imperial kingdom is rich and secure,

where none are third or second – all are one;

They do this or that, they walk where they wish,

they stroll through fabled palaces unchallenged… “

——————————————————————–

.

.

.

.

.

**Ropani is a work song sung by women working in the fields.

***Trans: used as a wider umbrella term to refer to all trans identities–trans femme, transexual identities– including hijra, kothi, kinnar, aravani etc. whether or not their government identity cards reflect the same.

In this essay:

Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi(DBA) are not a homogenous group in any way. Muslim Dalit-Bahujan women are considered in this term due to caste inequalities that exist within Indian muslims.

I have used third person words like ‘they’, ‘them’ in many places to refer to D-B-A collectively since I occupy the Bahujan(OBC) place in the D-B-A. Use of ‘us’ proposes a possible threat of conceptually homogenising the D-B-A women and their struggles.)