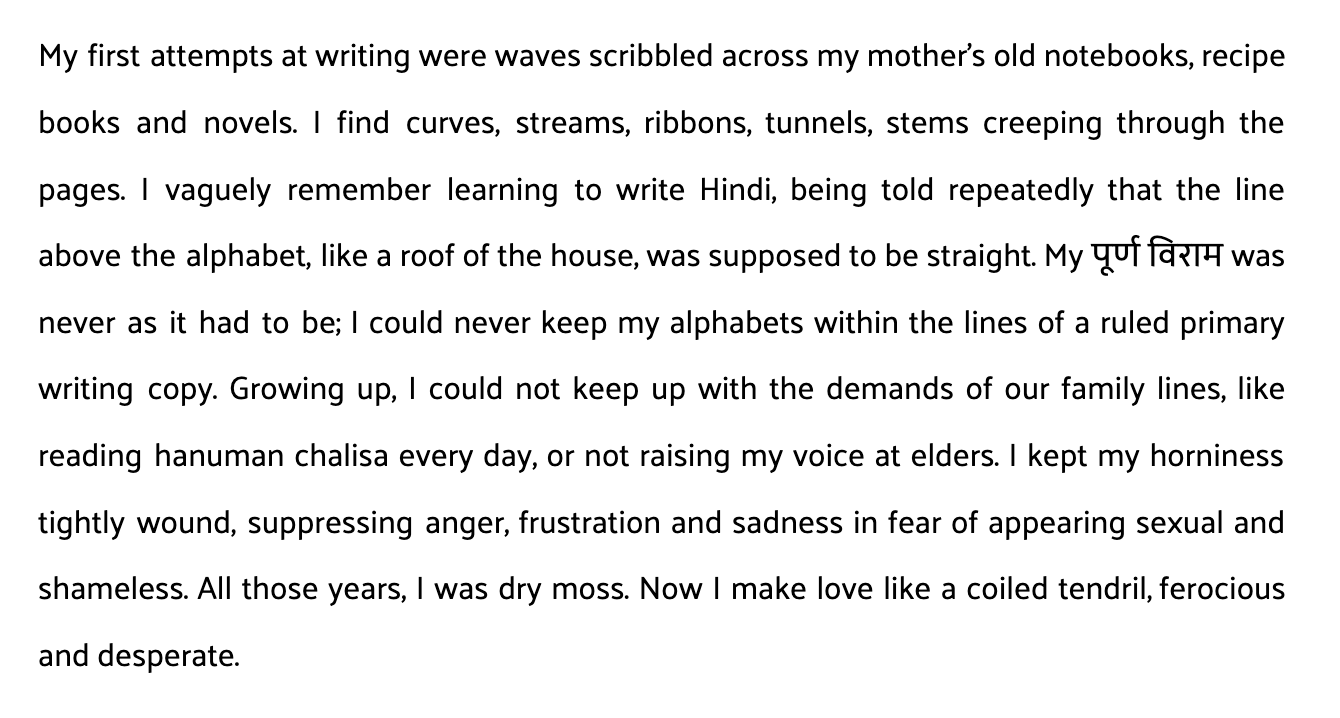

The gestural marks of abstraction helped me to articulate the waves of feeling that exceeded — or at the very least resisted — language. -Ara Osterweil Between Her Body and the Stain

The paradigm of the wave is interdisciplinary. It permits an investigation into time, bodies, forms, and languages. It permeates desires of formlessness in writing, flesh and movement, and stages with force, many awkward encounters with memory. It reigns high over certain periods of your life, colouring them indiscriminately: years looped together toward a single movement of emotion. Waves can also cause insurmountable damage. They can compound an already unfolding atrocity, or take our attention away from movements that matter. They take away rights from those who can still claim to enjoy them. And then there are those whose tragedies have almost no bearing upon the world of the living. They are left locked up, a border island within the city.

*

First wave: The hard sinking of a heavy stone down the oesophagus, which I usually associate with my father’s presence. When we were children, my brother and I recognised the sound of his heavy leather slides, and nose-dived into our books whenever he was around our room. I tricked my brother once, dragging the chunky brown slippers with my small feet—found him shuffling into place and dropping his tiny phone, scared like a cartoon cat.

Second wave: I hear vessels crack inside my abdomen, pain intensifies then releases for hours like a creature breathing. It brews in my lower back, ripples of pinching pain. Another pain emanates during clitoral orgasm.

Third wave: The same vessels once found cracking, wrung like clothes, splash over the bed. For a few seconds, I feel powerless, surrendered, cocoon-like, as pleasure and relief spread through my legs.

The body, like water, harbors sensations in waves.

I characterise the initial phases of mourning in my body through numbness:

I did not feel strongly about anything except the terror of having lost him. I ate whatever I could find; there was no sexuality in my body anymore. Being in grief was stillness. I recall that period as my body craving emptiness.

In May 2023, a week before the semester exams, my cousin brother died in inexplicable circumstances, four days before his twenty-third birthday. I am twenty-three now and we are inching closer to that date.

Ten years ago my grandfather too had passed in the month of May. I remember snatches from his death: clamour of constant company—relatives, and friends—bodies sprawled across the floor on white mattresses, weeping. I felt both their memories rising together in a chorus, throwing me into a grief cycle that lasted one and a half years. A year after his passing, I went to a beach for the first time and found the ocean shore exactly like I knew my body: a palimpsest of experience. I could dig both of them till the point of exhaustion, but memory would not end.

*

What is a wave? Can we be one?

In our post-pandemic lives, waves have become markers of time. We remember our experience of the pandemic through the waves that constituted it. Wave plays a pedagogical function; we understand intensity through it. It allows us to measure devastation, justify death. The first wave of COVID hit India in March 2020, spurring the country into lockdown. I was part of the batch of students graduating class XII that year, and we were taking our Board examinations between February–March. The months before the pandemic hit were months of harsh winter and a crackdown on dissent by the right-wing government in India. People had taken to the streets in large numbers to reject the Citizenship Amendment Act and National Register of Citizens, bills which excluded Muslims from gaining citizenship to the country. Many of us in school were following the CAA protests very closely, discussing them in corridors, weary with a restlessness over our inability to join any protests. Our school was located inside the Western Air Command of the Indian Air Force. We were protected from any political ferment and far, far away from sentiments of state criticism. These are lines from a poem I wrote at the time

Pre-board II exams were to start in a week,

Priyanshu sat on a desk in Munirka

which trembled with shock from adjacent JNU.

He checked Twitter every five minutes

while EM waves danced senselessly in front of him.

While the rest of the poem is heavy with grand metaphors of rage, it turns a quiet corner here to focus on a character who was based on my friend, Priyanshu. Newspapers and television news were not accurately covering day-to-day incidents of state violence. Many messages about protests and organising were circulating on social media through WhatsApp and Twitter. People were also following reliable independent news reporters and influencers posting regular updates. Payal Kapadia’s ‘A Night of Knowing Nothing’ poignantly assembles a montage of these handheld smartphone camera videos from Jamia Milia Islamia, Jawaharlal Nehru University, and Aligarh Muslim University. The jarring shots of police officials ransacking libraries, lathi-charging on protesters are played without editing the picture or audio, as a testament to practices of remembrance and record-keeping in the hands of the public.

Alas, the CAA-NRC uproar, Shaheen Bagh protests, and student protests were soon forgotten as a wave of the COVID pandemic overtook the country. The idea of the pandemic citizen has been well articulated by Dhiren Borisa and Gavin Brown in a chapter called ‘Contagion, Containment and Communalism’. They argue that the lockdown was a strategy of containment, not just of the virus but of resistance and dissent against the state. The sit-in and protest sites were cleared as the lockdown hit, and protesters were imprisoned under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act. Adhering to the lockdown and policing activities of the state ensured a good pandemic citizen. The wave of authoritarianism and disease came hand in hand, one complementing the other.

In June of 2023, I joined a batch of body movement classes being offered by my cousin sister and performance artist, Jasmine Yadav, in a studio in Malviya Nagar. Thus began my lessons in wave-making. A phrase that she used a lot during the classes was ‘melting to the floor’. One would try to completely lose the stiffness of their body and collapse to the ground. We flowed through the studio space in our plasma-transformed bodies, truly forgetting for two hours what it meant to be oriented as humans: straight and upright. Reading Sara Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology now, I recall the sessions as a re-orientation of the body towards the world around it. Forgetting normative movement we experimented with what could be animalistic, queer or antagonistic bodies in play. Most yoga asanas we learnt in class were named after animals or reptiles: lizard, frog, cobra, locust, cat, dog, cow. Perfecting the pose meant getting as close as possible to the non-human. We moved through the studio space as if we were all waves. To create a wave is to extend something to the furthest point, then witness its fall. I made myself fall repeatedly, finding permanence in it. Through wave-making in my body, I was slowly shifting the numbness so characteristic of grief that had settled in me.

To think of the wave as something intrinsic to our bodily experience, I turned to Virginia Woolf’s 1931 novel, Waves. Woolf believed that our bodies resemble water, and around us are porous tunnels leading to a cluster of connected experiences. ‘I ripple I stream’ (76). I took long walks in the neighborhood park the winter I was reading Waves.

Notes from January 8

Shadows take over as I walk through. Dark tree foliage hovers over me, and banyan roots hang around. Winter trees, leafless, extend over the landscape like tunnels. All materials at once become transferable, porous, in the darkness. Shadows streak through the gravel path while flowerless snake plant varieties or wild dracaenas growing in bunches spread through the land, tentacular. The park is mostly empty at this hour, and there are unlit patches where I am surrounded by dark bushes on both sides. On these sterile winter evenings, I walk alone and forget that I am a woman. In my father’s family, women are only as good as their expendable bodies. My paternal grandmother, on a perfectly ordinary Sunday, yearns for an uneducated daughter-in-law (8th pass, she says) in place of my mother, so she would never leave the house or work a job, to serve her at home all day. I end the walk prematurely after the second round, as I can see no one else in the park. Darkness can help me disappear, can never make me forget I am a woman in this world.

*

I want to read every word with him.

Just as the River Gaular sweeps past Sygna and narrows to a waist, suddenly cascading into a wide, powerful waterfall, so strong and foaming white that the river no longer resembles water but looks like a falling mountain, you can see Storehesten rising to a high, bluff summit, as if the peak is collapsing and reaching up at the same time, it’s just an illusion; you see the mountain through shards of water splintering in the air. The boy stands on the slippery rocks just below the waterfall, its vapour sprinkling his face and hair, small droplets of moisture beading his jacket and trousers, and the water soaking him as he stands there in the sun.

– From Bergeners by Tomas Espedal

How much could we learn from drinking only water? Han Kang’s protagonist persists into a border area between states of being, by becoming a vegetarian. She refuses to ‘maintain’ herself according to what is expected of a woman—made up, full-breasted, healthy, ripe. None of the characters can understand the vegetarian’s drastic decision and the fact that it was inspired by her dream. She refuses to explain herself and cannot be bothered by the conventions of the hospital, family, or a largely meat-eating culture around her. She is diagnosed with schizophrenia. Human order refuses to accept or understand her interspecies dream of becoming one with the trees outside.

Can I move from one medium to another?

From human shadow to plant membrane?

Between us, I find a cluster of stems growing. Can they carry the words from my head as I comprehend them? Water keeps moving in the text. It is in different shapes, splintering, yearning, narrowing like a photograph, splashing on a blank page. Sometimes words are part of a form that cannot be shared. Fragile visuals appear, but I cannot translate them to language. When we are young, we communicate through instincts and gestures, haptic and aural tendencies. Underwater, I enjoy the silence till my chest pounds and trembles, forcing me to come up for breath.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

References:

- A Night of Knowing Nothing, 2019.

- Banerjea, Niharika, Paul Boyce, and Rohit K. Dasgupta. COVID-19 Assemblages: Queer and Feminist Ethnographies from South Asia. Routledge India, 2022.

- Espedal, Tomas. Bergeners. Translated by James Anderson. Seagull Books, 2017.

- Han Kang. The Vegetarian. Translated by Deborah Smith. Granta Books, 2015.

- Osterweil, Ara. “Between Her Body and the Stain,” 2017. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/between-her-body-and-the-stain/.

- Woolf, Virginia. The Waves. Penguin Classic, 2000.