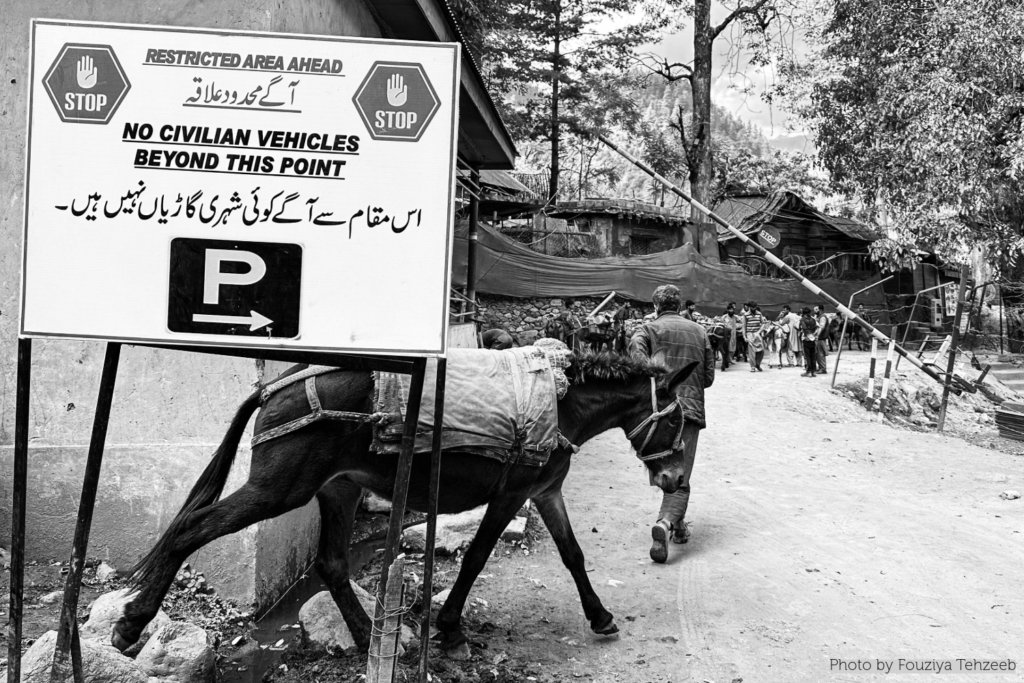

After nearly three years, I came to see you. I was certain that you would overwhelm me by the massive military presence, the series of checkpoints, the frisking, and having to prove my identity to those guarding you. Yes, it did, but I really wish you didn’t. This time I was surprised that the road leading towards you has become tech-savvy; instead of being excited, it made me insecure.

“What do you do with all this data?” I asked the first soldier I saw, who took my photo with an ID-card held in my hands. He reassured me that all the data would be deleted by the end of the day if my friends and I returned back as a whole package in the evening. On the way I heard, a few young men had violated your boundaries, and now there are strict measures in place to protect your sanctity.

Let me first clarify that I’m not a mad loverof you nor do I like you. That’s why I won’t address you as ‘Dear’ or refer to this letter as a ‘Love Letter’. However, I would like to call you LOCK (Line of Control Kashmir). I’m not seeking permission because you don’t have much of a choice to reject it; you are created and controlled by a crazy crowd.

So, LOCK, do you recall the first moment when you were created and drafted on paper? How did it feel? How did it feel when you were given the name? I’m curious to know.

I can share with you the stories of people when you were born. I can tell you how they felt when you were building a space for yourself, cutting through their river, corn fields, and forests. I can recount tales of families shattered by your announcement, your uninvited arrival.

This includes the story of my grandmother, Hajira as well. You took away her last desire to pay a visit to the graves of her two brothers. I doubt she ever thought of travelling to Mecca to visit God’s home more than she wanted to see those graves. You are a wretch!

I hear many tourists come to visit you now. I wonder whether visitors from different parts of the nation think you are wretched. Perhaps ’Border Tourism’ was initiated to make you excited and help you forget the seventy year long trauma that you endured. Many non-locals visitors would adore you when they stood on your last stepping stone. What voices do you hear? Do you feel proud of yourself?

Does the gushing water in no-man’s land hear the silence of a native’s heart?

You are not alone in having witnessed and perpetrated acts of violence, so don’t worry. I’ve heard that McMahon Line and Radcliffe Line, your “international friends,” are also on the same ship.

In her book “Midnight Borders’, Suchitra Vijayan documents the stories of people who paid the price of this nation making process. ‘Caught between history, time and territory, they are the people who get trapped beneath the collapsing lines that willed nations into existence. They are the unacknowledged casualties when those arbitrary borders shift, even a little’.

LOCK, she has written a story about Ali from Jalpaipuri, West Bengal. I imagined Ali living under the solar eclipse when I read that. Instead of the moon blocking light, Ali blocked the floodlights on the border with newspapers. It had affected his physical and mental health.

You see, you and your friends are like a glass jar with defined contours and a lid with a small opening. People can see through you the divided villages but are locked inside. The open lid is maybe a small space through which exchange or an act of resistance is becoming possible. It’s a space through which Ali sent her wife K. back to her home in Bangladesh to live happily.

You see, you and your friends are like a glass jar with defined contours and a lid with a small opening. People can see through you the divided villages but are locked inside. The open lid is maybe a small space through which exchange or an act of resistance is becoming possible. It’s a space through which Ali sent her wife K. back to her home in Bangladesh to live happily.

Oops, I seem to have crossed the line with you. Resistance is not something we should discuss.

I’m not sure about this but we can talk about the climate crisis. Suchitra also wrote briefly about the climate crisis and borders. Floods and forest fires are a common phenomenon now. Does it worry you, LOCK? There is a risk that your boundaries will get altered too. But I hope that, like most others, you are living in denial regarding this.

As I drove close to you, I observed local men tying large blocks of cement bricks on the horseback. They all work with the army units as daily wage workers. Sunflowers were growing in abundance in this last village. People were waving to each other on both banks of the river. The signpost indicated that Islamabad is 407 km from here, whereas, Delhi is 930 km away.

On the other side, shouting, was Ayaan, a little boy, in an orange T-shirt. He called out loudly that he was from Multan.

We both were struggling to decipher each other’s names. Shouting at the top of our lungs, he and his family couldn’t hear us clearly. We stood on the last stone there but couldn’t toss a paper with our names tied to a pebble, across the river. LOCK, at that moment I felt the immense weight of your grip. But it was a beautiful act of resistance to connect with Ayaan and his sister Dua. Dua was attempting to reveal her name to me while folding her hands. “Okay, I will pray for you”, I shouted, and seconds later I realised it’s her name. Humans always respond and find ways to do that.

I crossed your line again.

In this letter, you can sense that an overthinker monster knocked on my door tonight. Do you also overthink about your future? I am asking because your existence is contested between two nations. I wonder if you face existential crises on some days like me.

I don’t know whether my relationship with you would transform, but write to me about your power and stories of individuals who tried to violate it.

Good luck.

Your Violator,

-F