The protest against the Bodh Gaya Temple Act of 1949 continues at the Domuhan grounds, the first hearing of the writ petition filed in the Supreme Court—initially scheduled for 24th March—has now been postponed to 16th May.

This protest is against the provision of BT Act, 1949 that mandates four out of eight people in the Managing Committee of Maha Bodhi Vihar to be Hindus, predominantly Brahmins. Led by All India Buddhist Forum (AIBF) and many Buddhist groups from all parts of the world are a part of the anti BT Act movement.

The roadside sign directing towards the Mahabodhi Vihar, Bodh Gaya (which is now called ‘Buddha Temple’).

Images of Buddha and Dr. B. R. Ambedkar at the protest site.

On the 37th day, bhikkhus, bhikkhunis and supporters gathered at the protest site.

“When I dare to be powerful — to use my strength in the service of my vision, then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid.”

— Audre Lorde, Second Sex Conference, New York, 1979.

In the midst of the wait for the hearing of the petition/action taken by the Bihar government, many women continue to participate in the movement, stepping into various roles and responsibilities that form the very heartbeat of any collective resistance. They collectively hold the vision of having the MahaBodhi land free from any Brahmanical control–either in the Management Committee or in the way rituals happen inside the Vihar’s premises.

A group of women sitting at the local shop near the protest site.

Two women at the Domuhan grounds who have come from Maharashtra to be a part of the anti-BT Act 1949 movement.

Footwear kept aside.

A group of women occupying the protest site to express their support.

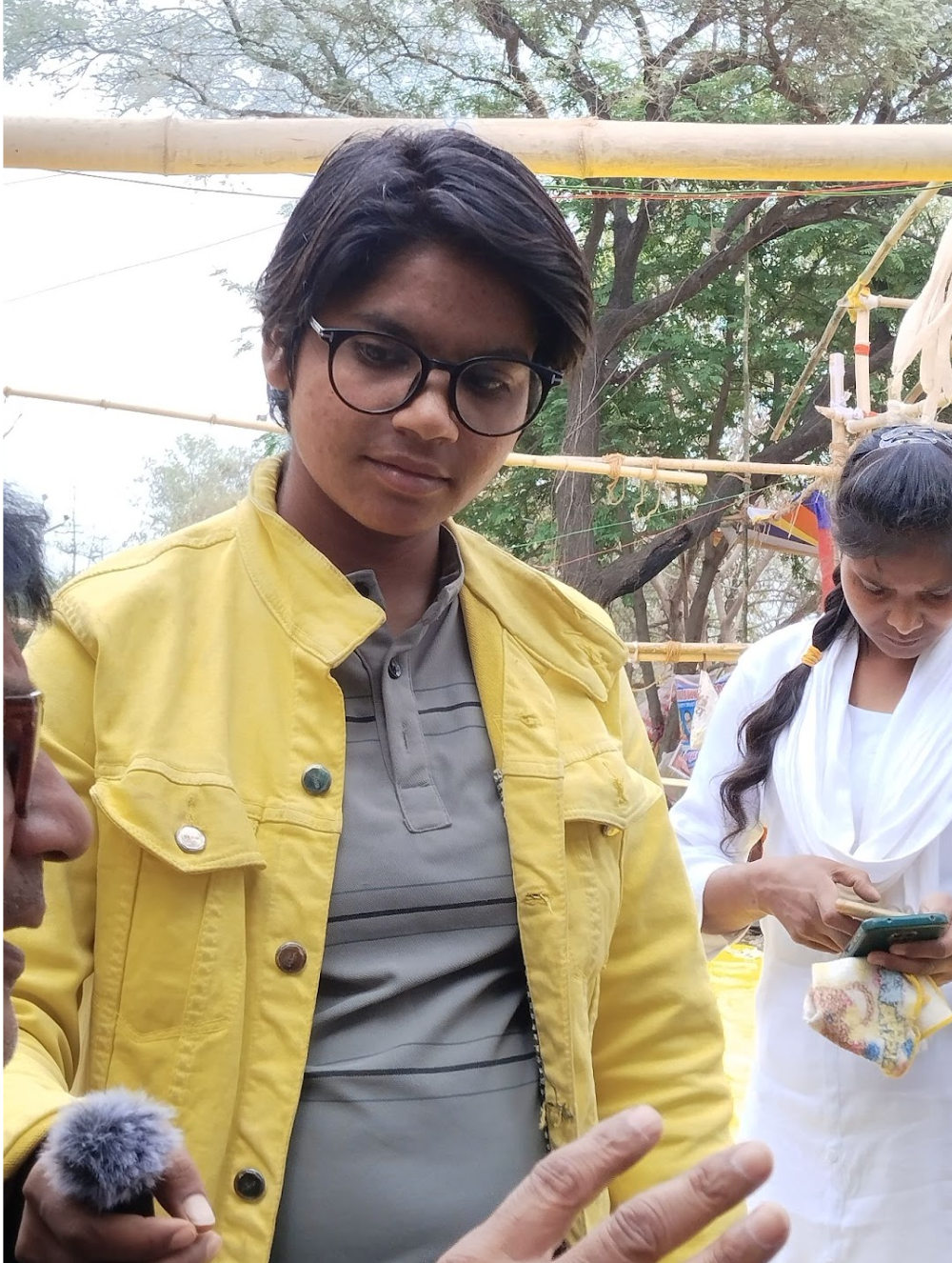

Twenty-six-year-old Roshni has been a constant presence at the protest site. Camera in hand, she has been documenting every chant, every pause, every moment as it unfolds under the open skies of Domuhan. Roshni is unlike a journalist that one sees in metro cities– one who is working with the organisational support of a media organisation, who does not have to fight an added/extra battle to prove herself as a media practitioner with most people she interacts with.

Speaking to me about the beginning of her career, she says, “The first interview of my journalistic career was in 2019 with Babasaheb Ambedkar’s grandson, Rajratna Ambedkar, at Ambedkar Bhawan in New Delhi.” Roshni feels very deeply about the Ambedkarite movements. She adds, “I’ve covered many stories and travelled to several places for my reports, though not all of them are available on my YouTube channel.” She takes a breath, sighs and tells me, “Life has been tough!”

Her channel, titled ‘Roshni ki Reporting’ has a background poster with images of anti-caste, feminist leaders of India. Hailing from Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Roshni’s professional life is far from the glamorous world of media that occurs within AC rooms of New Delhi.

Roshni in a yellow jacket, recording bhante Pragyashree’s address al on the 37th day of the protest.

She used to work as a helper in a dusty Noida factory that produced parts for cars and bikes. Her hands bore the proof: rough, calloused, and lined with cuts from long hours on the shop floor. That’s how Manoj Antani remembers first meeting her. “Her hands told the story of hard labour, but her eyes—they were full of questions. She had the spark,”“ recalls Antani, founder of the YouTube channel ‘Samta Awaaz TV’. It was he who handed Roshni her first camera and mic. “Guruji taught me how to hold a camera, how to do reporting…” Roshni tells me.

She started by reporting for his channel, learning not just technical skills, but how to see stories where others saw silence. “I reported for his channel, and then I made one of my own,” she adds. That channel—‘Roshni ki Reporting’—now stands as a digital diary of dissent.

Roshni is conducting a live interview from the protest site.

Roshni is speaking to her ‘Guru’, who was also present to cover the protests for his YouTube channel.

Early on, even her family resisted her decision to pursue journalism. “They would say, ‘You’ll travel far, stay out overnight—who what else…. This isn’t right for girls,’” she recalls. Roshni candidly spoke about the challenges she faces as a woman reporter—issues that often remain invisible behind the camera. From struggling to find clean washrooms to ensuring her safety while travelling alone, the path is never easy.

Beyond these societal hurdles, Roshni highlights a challenge specific to her own journey: the lack of a formal journalism degree. “No matter how good my work was, I wasn’t taken seriously,” she says. At press conferences, she was often treated with disdain—“worse than a small-town wedding photographer,” she adds, with quiet hurt. She observed a clear difference in how women journalists from metropolitan media platforms, armed with formal education, aesthetics of language and credentials, were treated—with respect and legitimacy. Determined to change that, Roshni enrolled in a postgraduate degree in Mass Communication at Awadh University in 2023.

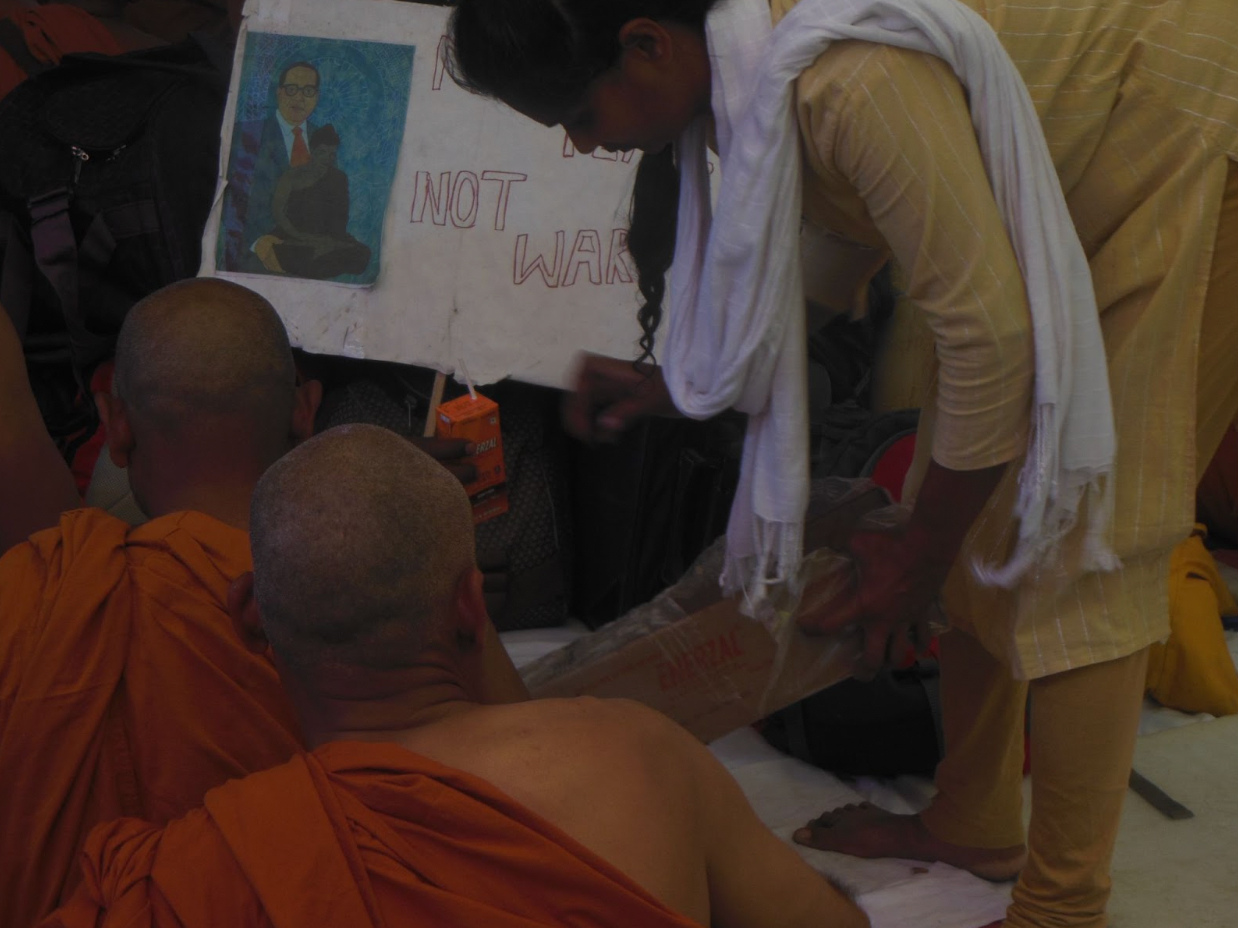

Another young woman, Gyaanti Baudh, can be seen at the protest site, taking on a variety of caregiving responsibilities throughout the day. She helps manage food distribution, making sure that everyone—including visitors—are fed. She ensures there is water for all, and later moves around collecting empty bottles from the protesters as they sit in silence during the maun.

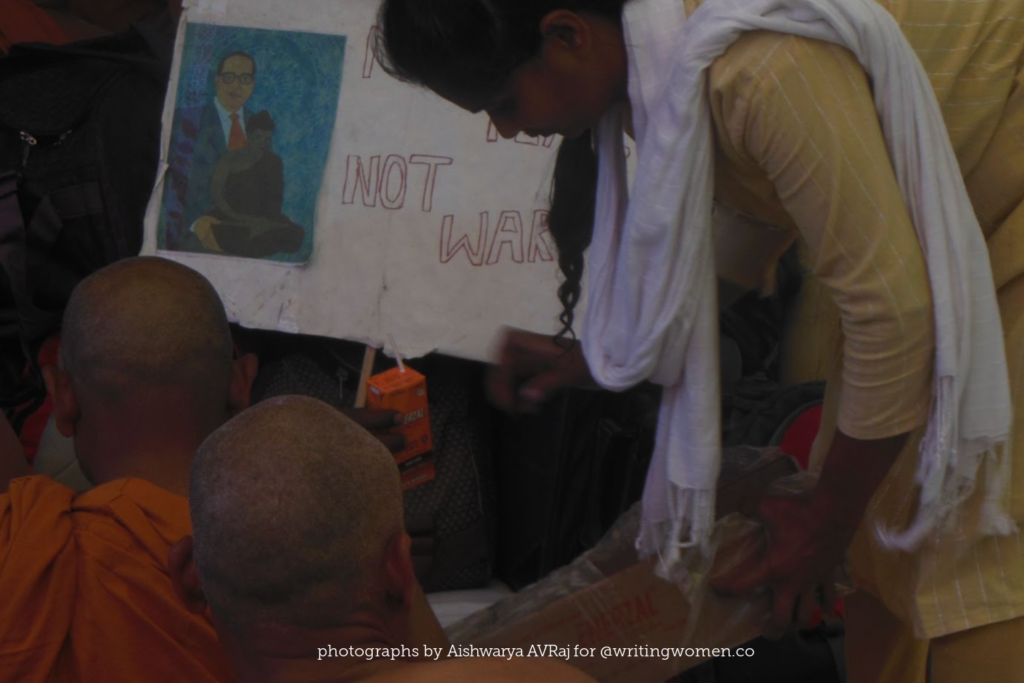

Gyaanti Budh collects used water-bottles. The poster in front of her reads: make peace not war.

When new monks and supporters arrive, she helps them find their way—directing them to places where they can rest, use the bathroom, or get a meal. She stays on her feet, moving from one task to another.

Gyaanti Baudh, dressed in a yellow salwaar, distributing electrolyte-drinks at the protest site. Her husband is also a part of the protest. However, the rest of their family does not support their involvement.

“My name used to be Gyaanti Gupta. One day I went to Arjak Sangh and was introduced to many questions. I began to read about the tussle between Brahmanism and Buddhism and India’s Constitution. I then decided I should not be called by my caste surname and I gave up on the use of sindoor and other things that symbolise slavery of women.”

She talks about her journey. A resident of Rohtas district of Bihar, Gyaanti Baudh has been a part of the Bodh Gaya protest since day one.

A statue of Dr. Ambedkar stands in a nearby park close to the Mahabodhi Vihar (temple).

“Dr. Ambedkar always said that progress of any community is known by the empowerment of women of that community. We had to be here, we are followers of Baba Saheb and Tathagat Bhagwan Budhha.” says 60 year old Vijaylakshmi.

The badge of the collective that Vijaylaxmi is a part of.

Vijaylakshmi came to support the protesters with 49 other members from the ‘Bodhipakkhiya Dhamma Foundation’. Having retired from the position of District Manager in the Social Justice Department, she worked with local Scheduled Caste communities—helping them secure financial support to start their own businesses. She was also responsible for training them in skills such as beauty parlour services, computer literacy, and other such vocational programmes.

Dressed in black-yellow checked kurti, Vijaylaxmi is checking her phone as she sits at Domuhan ground.

“Women have to be financially independent, She must be literate and determined to make her own decisions. Women should not be taking permission from her family to join any movement like this, she should rather be informing her family members about it.” She tells assertively.

Vijaylakshmi(second from right, in the group of sitting women) is speaking to a local reporter. She is accompanied by more women from Nagpur.

Roshni had earlier stated that for many women, joining protests away from home also becomes an opportunity to explore a new city. Echoing this, Vijlakshmi shares that she is in Bodh Gaya for just three days this time and she has managed to visit the ‘Sleeping Buddha’ statue so far, as her focus has mostly been on being present at the protest site. She adds that she’ll be returning on April 4th, along with other women from her group, to take part in the ‘Samrat Ashok Jayanti’ celebrations on April 5th at the protest site.

It is interesting to think about Roshni’s observation(which I agree with), “10-15 percent women here are OBCs and the rest are SCs”. Historically, haven’t the Savarna Feminists(who affirm Brahmanical tenets) viewed the DBA (Dalit Bahujan Adivasi) women as subjects of either sympathy, or charity or disdain or contempt–depending on their convenience and context of the relationship they have with them? However, the way in which women in Anti BT Act 1949 situate themselves–the clarity of vision, demand, assertion, culture–is not a first time thing. From Nangeli to Mayawati–the DBA women have ‘dared to be powerful’–in the everyday and in the less-ordinary, like the movement against BT Act 1949. I invite you to think of all those women–and if their work has been documented and re-visited enough times? What is the feminist history of India, if not distorted, without such a reading?