“Walls are publishers of the poor!” – this famous line by Eduardo Galeano, an Uruguayan journalist and writer echoes the ethos and exigencies of feminist publishing. Feminist, queer, anti-caste, labour, and other struggles of marginalised people whose voices have been historically invisiblised, whitewashed, or crushed find unconventional ways of translating their demands and resistance.

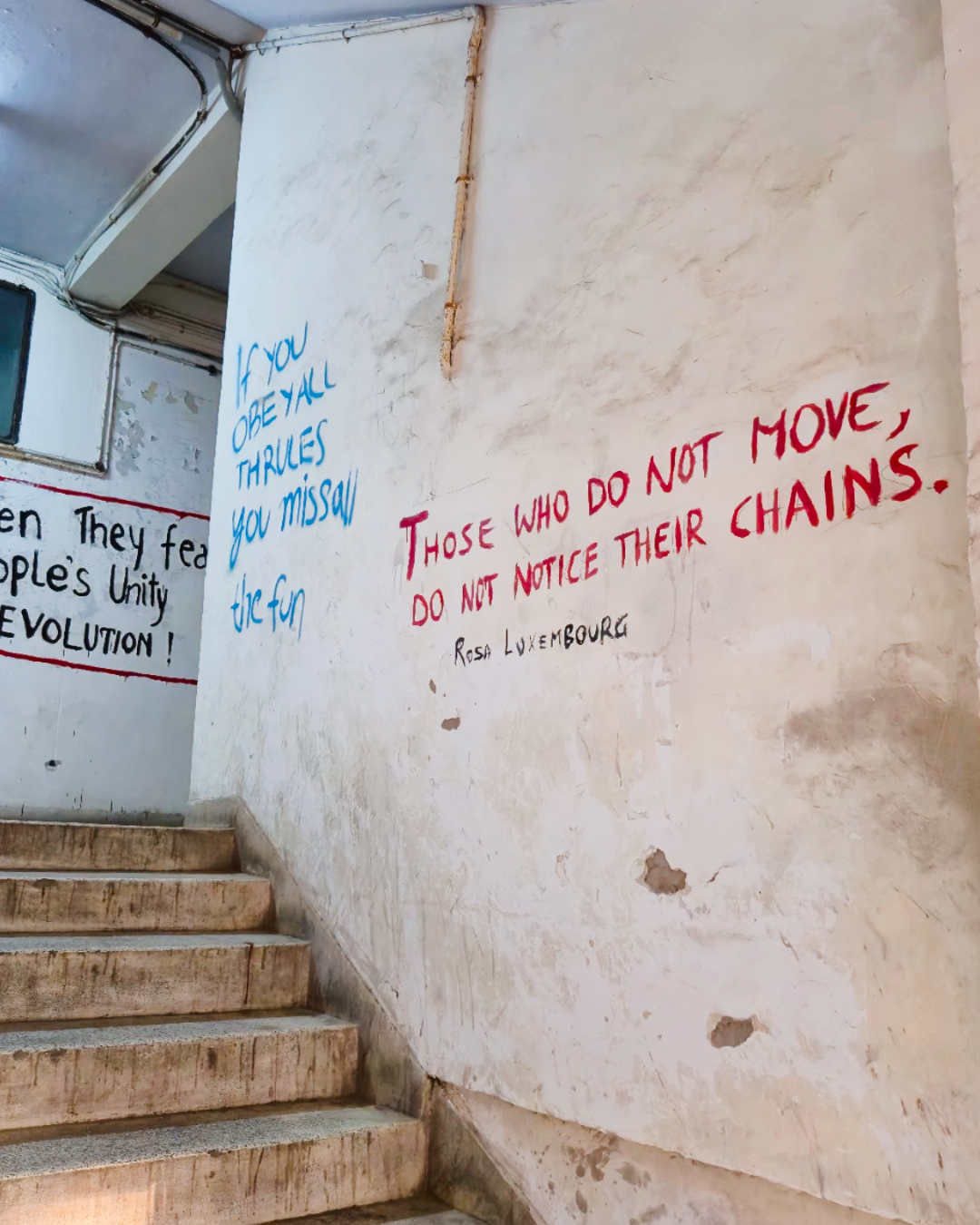

When I first came to Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), in the winter of 2016, it was the sight of these posters, graffiti art and pamphlets (parchas) that caught my attention. They were colorful and bright- vocalising stories of people’s struggles, resilience and resistance. Across the campus premises, there seemed to be an unapologetic display and celebration of feminist struggles and pro-people progressive politics. I had not seen anything like this ever before. The sight transported me to another world where my existence as a woman mattered. It was a world where I did not have to vocalise my emotions- the walls with all their glory, shrugged in their ruggedness, spoke for me. The sight of those posters stayed with me forever.

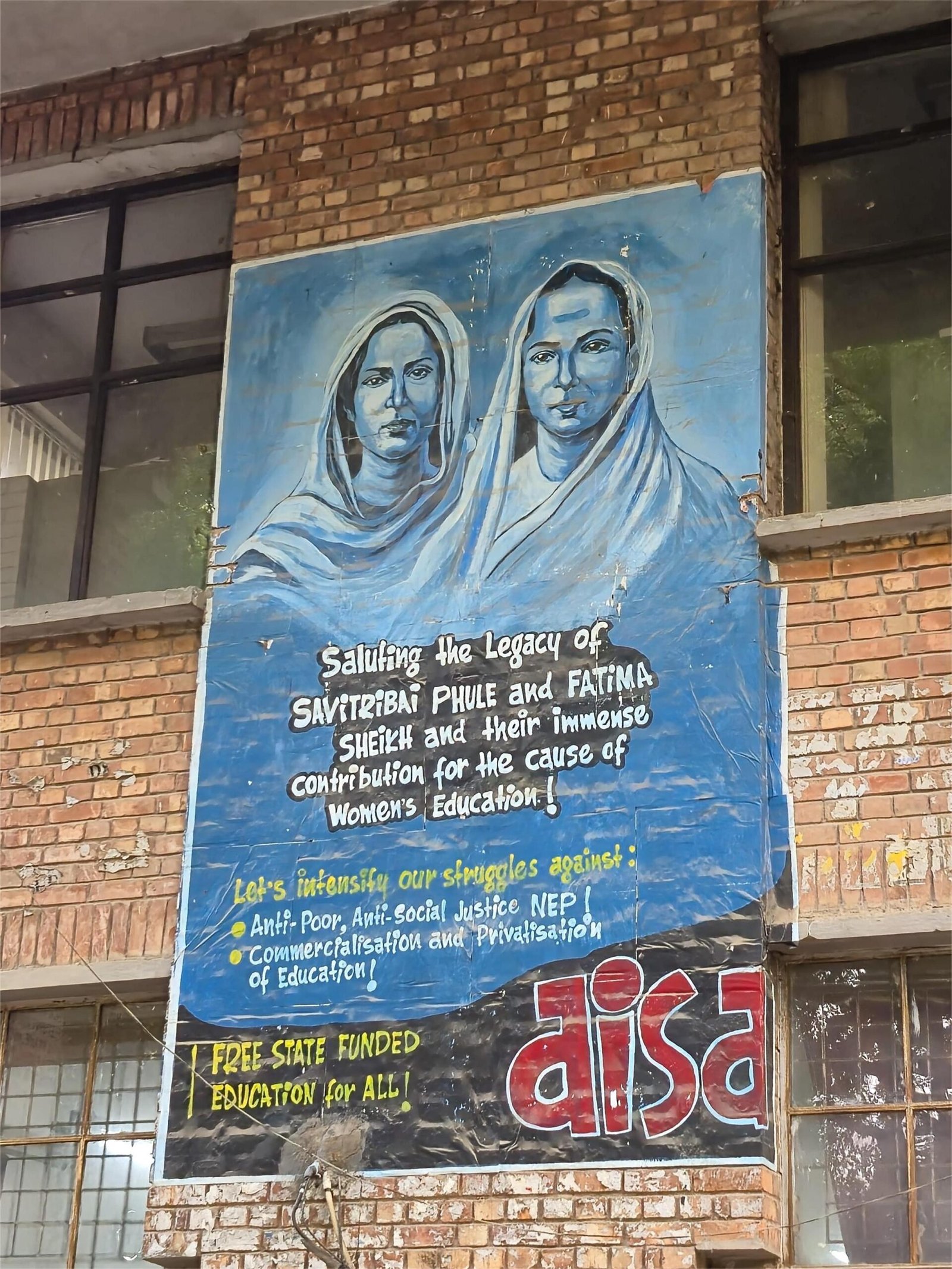

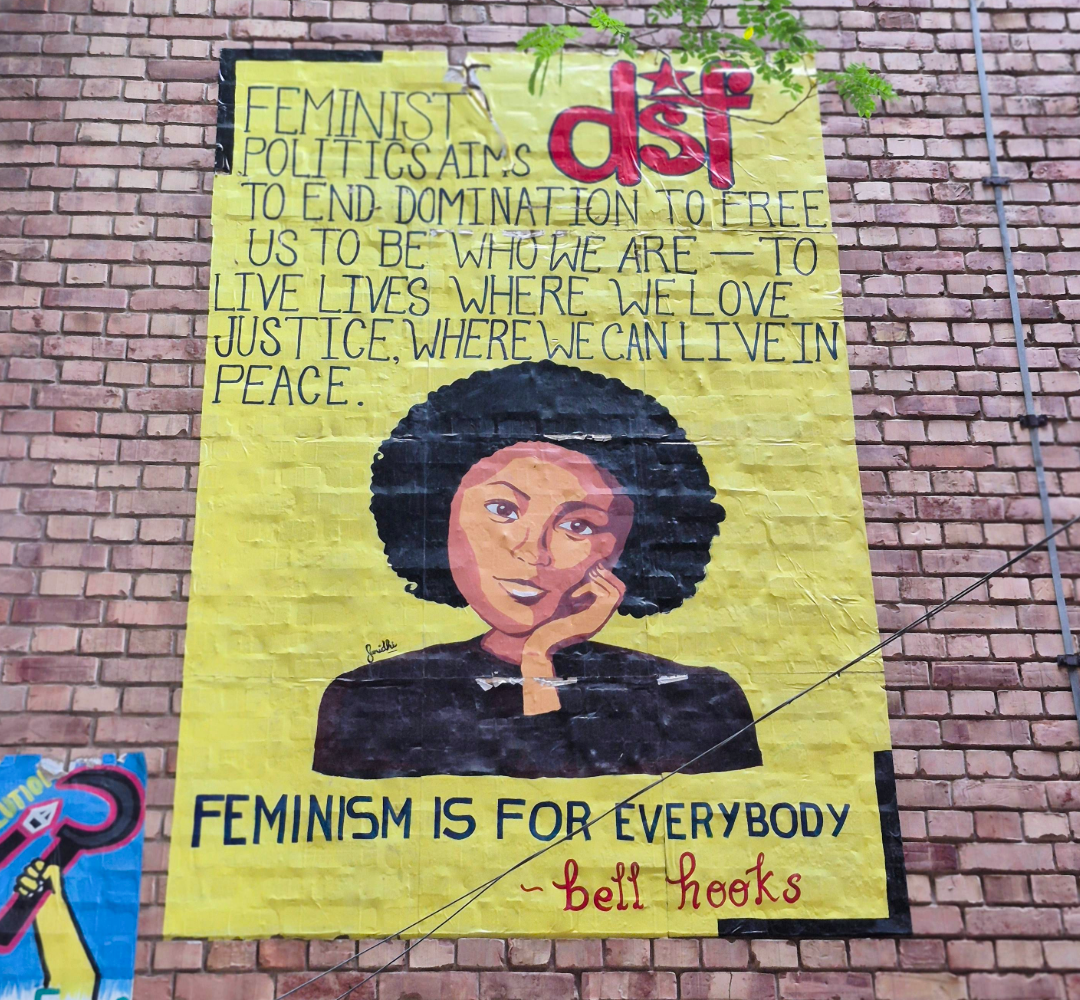

These posters translate feminist and queer resistance, raise slogans of anti-capitalism and social justice, and present pictures of revolutionary anti-caste figures. They are the products of student labour, love and rage. They are designed and created by students, collectively, as a way of translating their vision of an egalitarian world. Historically, this ‘poster-parcha culture’, has been an intrinsic part of JNU’s institutional culture, and its image as a hub of politically vibrant and pro-people activism. For years, these posters have given voice to generations of students and activists who made the walls their prime canvas of creative political expression.

Years after when I began my masters at JNU in 2018, the university’s right-wing administration issued a decree. All forms of creative expressions on our walls were to be considered an act of ‘vandalism’ and ‘destruction of public property’. The university administration tasked itself with getting rid of all the wall art in order to ‘clean’ and ‘sanitise’ the campus. Even amidst students’ resistance, the administration managed to denude the walls. A historically built institutional culture of learning and unlearning through wall art was put to rest.

At a time when the world shut down because of the global coronavirus pandemic, student voices refused to follow suit. In those moments when the world witnessed one of the worst crises, the students of JNU decided to reclaim their publisher- the walls that belonged to them. They materialised what Sara Ahmed in her The Feminist Killjoy Handbook says about vandalism as an indispensable feminist guerrilla tactic by “writing ourselves and our stories on materials that were not intended for that purpose.” Five years later, the fight for reclaiming JNU’s walls is ongoing. here have been multiple rounds of stubborn students laying claims to their walls and the administration retaliating by white washing and ‘sanitising’ them of any remains of resistance.

Today, embodying the spirit of the words of Avatar Singh Sandhu Pash, the revolutionary poet from Punjab- “Mein to ghas hoon, tumharey har kiye dhare pe ug aaunga” translates in English as ‘I am grass, I will grow out despite all your assaults’, the JNU walls beam with exuberance and resilience. Through summer’s bright sun, drizzling rains, and winter fogs- these walls stand tall, screaming and whispering. They talk of Savitribai and Fatima Sheikh whose fight for anti-caste education for all girls, and women’s social rights changed the course of the subcontinent’s history. They serve as a reminder of bell hooks’s emphatic words- “Feminism is for everybody.”

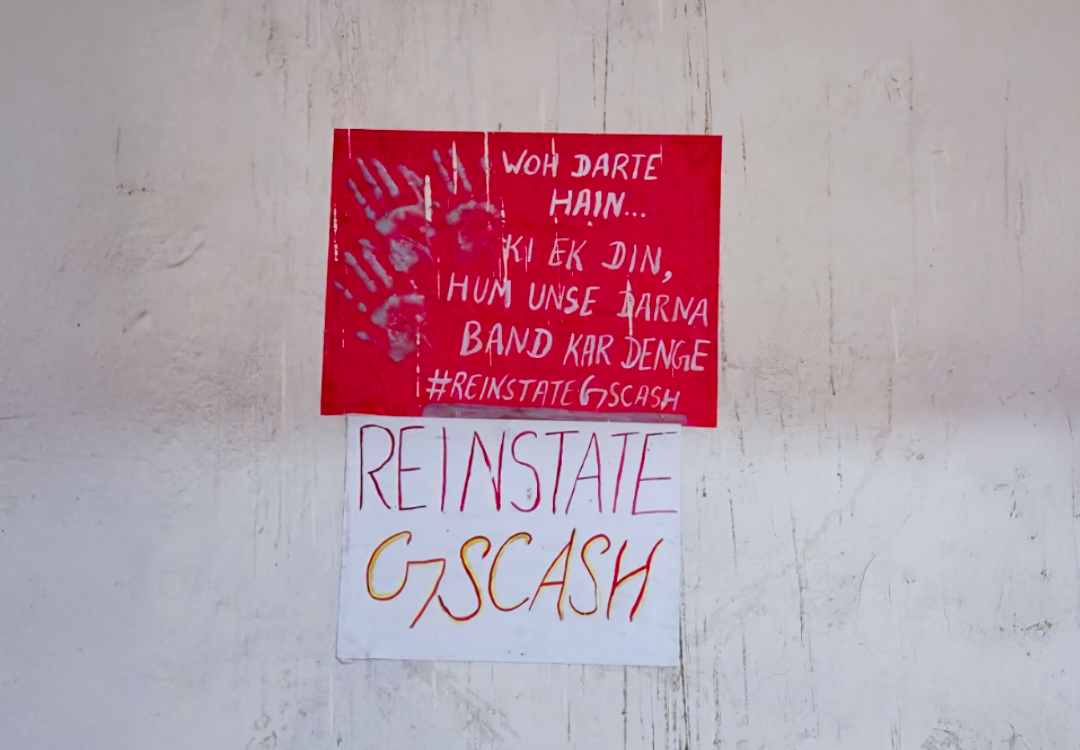

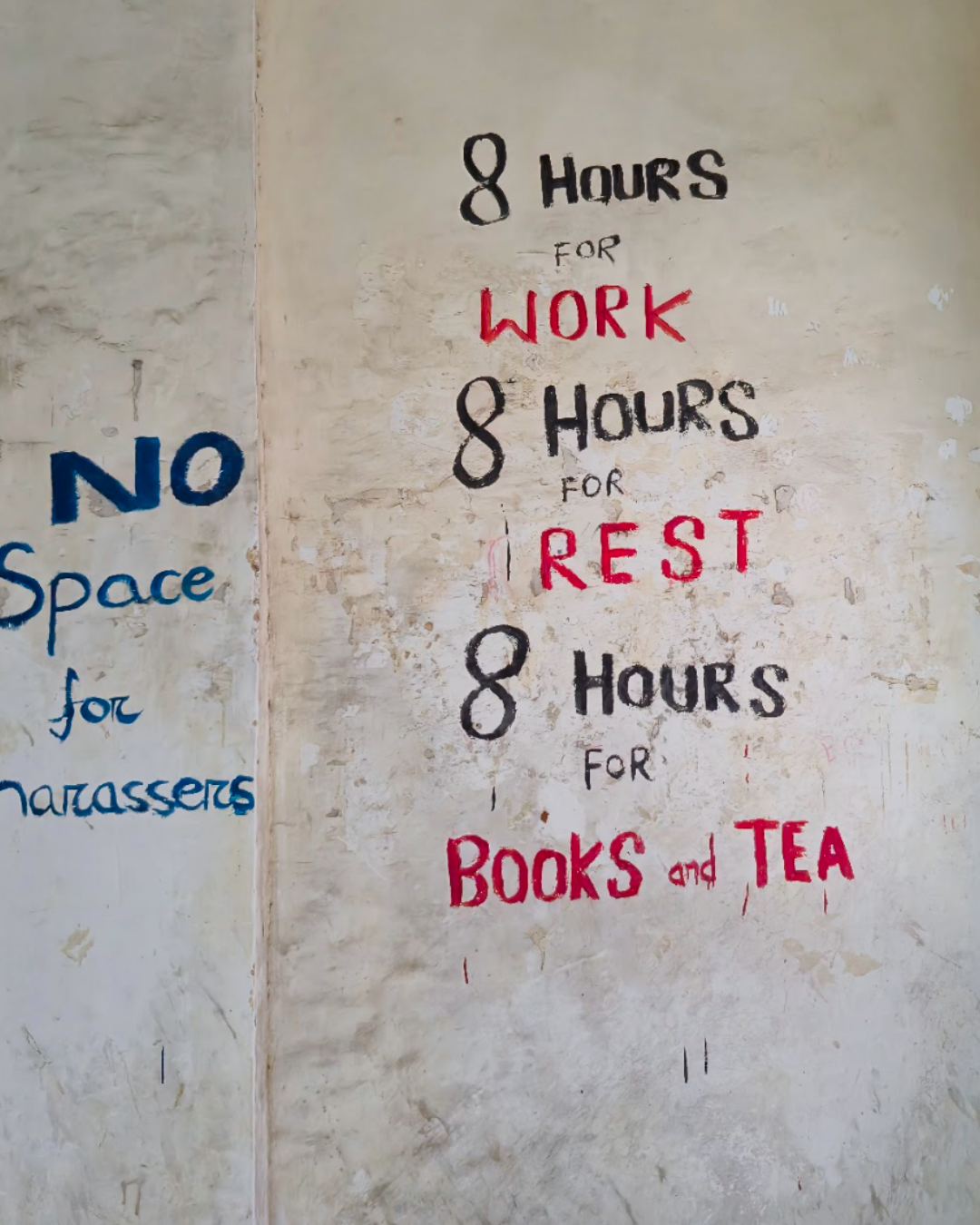

They echo Nangeli’s fight against brahmanical order. They visualise Dr. Ambedkar’s historic moment of burning of the Manusmriti and along with it, its casteist and patriarchal dictums. They chant the slogans for reinstatement of Gender Sensitisation Committee Against Sexual Harassment (GSCASH) on campuses which was dismantled by JNU administration in 2018. They demand “8 hours of work, 8 hours of sleep and 8 hours of books and tea”, resonant of the historical demands of the labour rights movement. These posters show a mirror to the discriminatory institutional cultures still manifest in everyday forms of casteism and misogyny in India’s premier educational spaces.

The fact that despite all the attempts to the contrary, this visual form of activism is still alive today, reveals the deeply entrenched resonance that it holds for JNU’s learning environment. Generations of students have come to know about many historical figures, movements and slogans through these walls, much before they were introduced to them inside the classrooms.

Walls, at least in a public institution like JNU, still continue to be the publishers of the poor, breeding dreams and aspirations of younger generations- marginalised along multiple axes, yet resilient in their visions of creating a better, more just future. Creating their own whispering and screaming walls is another step towards translating that vision, and realising that future.

(Images Copyright: All the images used in this essay are clicked by the author).