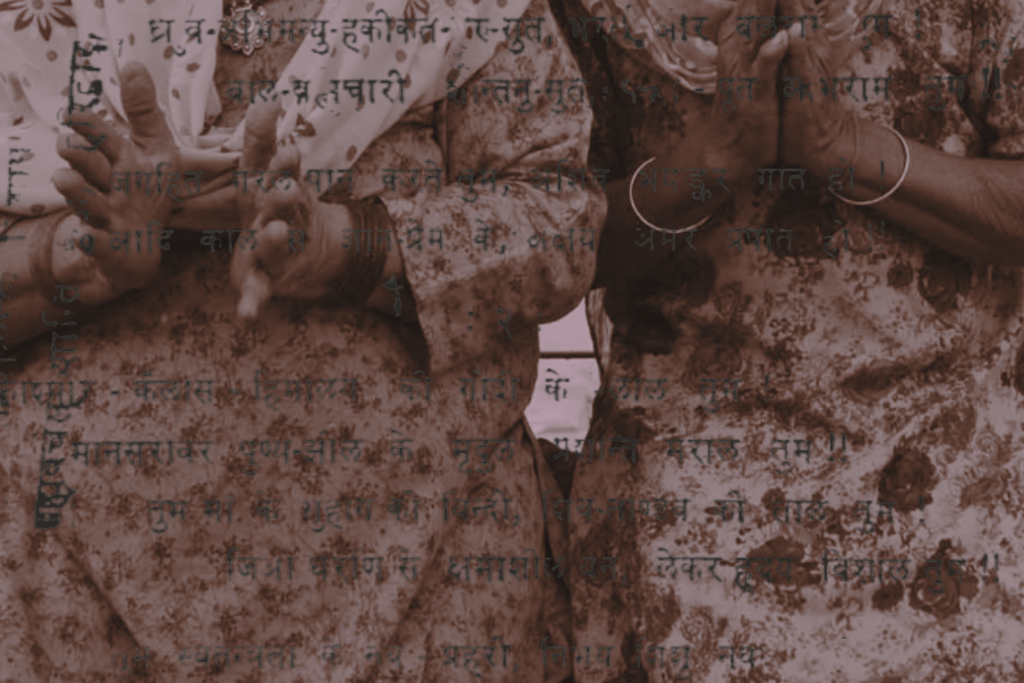

छोरी चली परदेस, मायका सुना हो गया, आंगन की कोयल भी चुप, गीत अधूरा हो गया।

Chhori chali pardes, maayka suna ho gaya, angan ki koyal bhi chup, geet adhoora ho gaya.

The girl has gone abroad/ away

her parents’ home is quiet/ empty

the cuckoo in the courtyard is also silent,

the song is incomplete.

I read ‘The Last Lesson’ for the first time in my twelfth-grade English class, somewhere between two poems already marked for memorization. I had no special expectations from it – just another colonial story, I thought, perhaps romanticized, perhaps tragic. But it began quietly. A boy named Franz, his feet reluctant on the path to school, the birds chirping louder than usual, the stillness of the streets. Something about that stillness stayed with me.

Back then, I didn’t know that stories don’t always scream to be heard. Some sit very quietly in starched Sunday coats, like M. Hamel, the teacher who announces that this is his last lesson in French. After today, all teaching will be conducted in German. The Prussians have taken over Alsace and Lorraine. French, the mother tongue of the people, is being banished. The class listens. Even old men come and sit at the back of the room. Too late, they realize what has been lost. A language. A rhythm. A home.

That day in class, I underlined one sentence in pencil: “When people are enslaved, as long as they hold fast to their language it is as if they had the key to their prison.” I did not yet know its irony – that even as France mourned the loss of its language in Alsace and Lorraine, it was enforcing French on colonized lands elsewhere.

But at that time, I wasn’t thinking of empire. I was a girl growing up in postcolonial India, fluent in English, hesitant to speak Hindi, and embarrassed by my grandmother’s accent. I had never known that language could be something you lose without even knowing it was yours.

When I was younger, I would often ask my grandmother to “say it in English” so I could understand her better. She would laugh, “Some things cannot be said in English.” I did not believe her then. I do now.

She sang lullabies in Haryanvi, not the polished kind you see in YouTube animations, but ones that smell of soil, ghee, and grief. They had strange rhythms, uneven like her breath, and spoke of waiting women, long summers, crooked men, and lost daughters. I once tried translating one for a school assignment. The English version came out clean. Rhyming. Safe. I showed it to her with pride. She looked at it and said, “Ismein wo dard kahaan hai, jo bolne mein aata hai?” (Where’s the pain that comes when I say it aloud?)

I didn’t have an answer.

Years later, I read Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?” and suddenly, everything made sense. Spivak argued that the voices of the colonized, especially women, are so often translated, interpreted, and softened that they stop being theirs at all. The subaltern can speak, yes – but no one listens unless she sounds familiar to the colonizer.

Translation, in that sense, is not always a bridge. Sometimes, it is a filter.

I thought of this when for one of my courses I read the court testimony of a Dalit woman who had been assaulted in Pune. Her original statement, given in Marathi, trembled with emotion as she spoke. It named casteism, community metaphors, and the names of gods invoked in desperation. The English version was clinical. “Subject” states that she was violated. She reported trauma. She requests justice.” What happened to her rage? Her gods? Her voice?

Translation had scrubbed her voice.

But language is not always lost to force. Sometimes, it is lost to convenience. In school, we were taught to “think in English” to avoid making errors. To improve fluency. We were told that using Hindi idioms in essays would cost us marks. The dialect my mother spoke – a blend of Haryanvi and Punjabi – was often met with giggles in classrooms and HR interviews. Someone once said, “So rustic,” I laughed with them. I shouldn’t have.

My grandmother would call English a bewaakoof ki zabaan – a language where people say “I miss you” and never return. A language, she believed, with too many exits and not enough homes. But I lived in English. I read in English. I learned about feminism in English. My entire vocabulary of resistance was borrowed from the same people who once banned my ancestors from speaking their language.

Was I still colonized?

When I read The Last Lesson again last year, something changed. I no longer saw it as a story about nations. I saw it as a story about women. About the quiet disappearance of what is ours – our words, our tone, our untranslatable selves. After all, it is women who hold language inside their bodies. In songs, gossip, lullabies, and curses. The way my mother once whispered, “shaant ho jaa, sab theek ho jaayega,” when I returned home broken after my first heartbreak. It was not about her words, it was about the way she said them. That tone does not exist in English. “Calm down” sounds like a command. “Shaant ho jaa” sounds like a lap.

So when a woman’s story is translated – in a court, a classroom, a book – what gets lost?

The lullaby becomes a poem.

Anger becomes a protest.

Prayer becomes a philosophy.

Everything becomes processed for a foreign gaze. And yet. Translation can also be resistance. A tool not just of erasure, but of survival.

When M. Hamel writes “Vive la France” on the board; it is not just a sentence. It is defiance. A man using the very letters that are being taken away to write a goodbye they can’t erase. I think of women who do the same. Dalit writers like Sujatha Gidla and Ajay Navaria who reclaim English and bend it to carry their history. Queer poets such as Mary Jean Chan who make the colonizer’s tongue stutter with metaphors it was never meant to hold. Translators who refuse to smooth over pain.

Feminist translation is not about perfect grammar. It is about loyalty. To emotion. To context. To anger. A feminist translator, like Spivak says, must “surrender to the text.” She must hear the breath, not just the word.

I once read a translation of a Rajasthani folktale in which a woman curses her oppressor not with violence, but with silence. The translator had written: “She looked away.” I tracked the original: उसने उसके नाम को हवा में छोड़ दिया। Usne uske naam ko hawa mein chhod diya. She left his name in the air.

Do you see the difference? In the original, she refuses to hold him. Even in memory. Even in syllables. In English, she merely looks away. A gesture. A blink. The violence of forgetting is lost.

I don’t know if I will ever write in my mother tongue. English has been too deeply sewn into my bones since childhood. But I write with caution now. With reverence. I don’t assume that I can carry eve ry woman’s story just because I have the words. And some, like my grandmother’s lullaby, must be left unfinished – sung in the dark, heard only by those who know where to listen. In The Last Lesson, Franz regrets not learning his language sooner. I regret not listening. I regret mocking the way my aunt rolled her r’s or how my neighbor added “the” before every word in English. I regret hiding my dialect as if it were a wound.

But I am listening now.

And I am asking, like Spivak once did: Whose language is this? Who gets to speak? Who gets translated and who gets erased? Because as long as women are speaking – in Bhojpuri, Khasi, Malayalam, Maithili – and as long as we carry their words across borders with care, rage, stillness…

We still have the key to the prison.

We still remember the way to our home.

.

.

.

References:

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the Subaltern Speak?

Daudet, Alphonse (1880). The Last Lesson.