The Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 ignited one of history’s largest forced migrations and with it, a wave of violence that would leave women particularly vulnerable. Feminist researchers have documented women’s experiences during this period but fiction writers have not been far behind in basing their stories on the experiences of women during Partition. Stories of widowhood, kidnapping, rape, recovery and restitution of women help weave a tapestry of female suffering and strength. These stories, primarily based in western India though a few venture eastward, delve into the complex emotions of women navigating the chaos of Partition. Confusion, uncertainty, flickers of hope, detachment as a coping mechanism, assertions, submission to patriarchal machinations all find expression in these stories.

In “Jadein”, Ismat Chughtai introduces us to Amma, the protagonist and matriarch of a family. When all her children and grandchildren leave town because of growing violence against Muslims, Amma refuses to leave and stays behind. It is an instance where a woman refuses to follow her family’s decision. Amma is an example of the women who showed an indomitable spirit in the middle of a war in a patriarchal society. But the house where she had lived in for 50 years since her marriage, growing roots, is like an aged tree. This house is her sanctuary, a world far removed from the wounds and the rivers of blood that the British had left behind. She prioritizes her emotions for the home over relative safety and stands her ground even in the face of mortal danger.

Lalithambika Antharjanam’s “The Mother of Dhirendu Muzumdar” is another story representing the women who fiercely asserted their agency and identity, but at the same time founda change in their status and identity. Shanti Muzumder proudly introduces herself as a former resident of East Bengal and a mother of nine children, all tragically lost during Partition. She eulogises motherhood and highlights the courage and sacrifice it demands. Yet, she also candidly acknowledges the internal conflicts mothers face when torn between the conflicting ideologies of their husbands and children. With deep sorrow, she laments her transformation from a proud mother of freedom fighters to a marginalised refugee, an outsider, and a beggar woman in her new home.

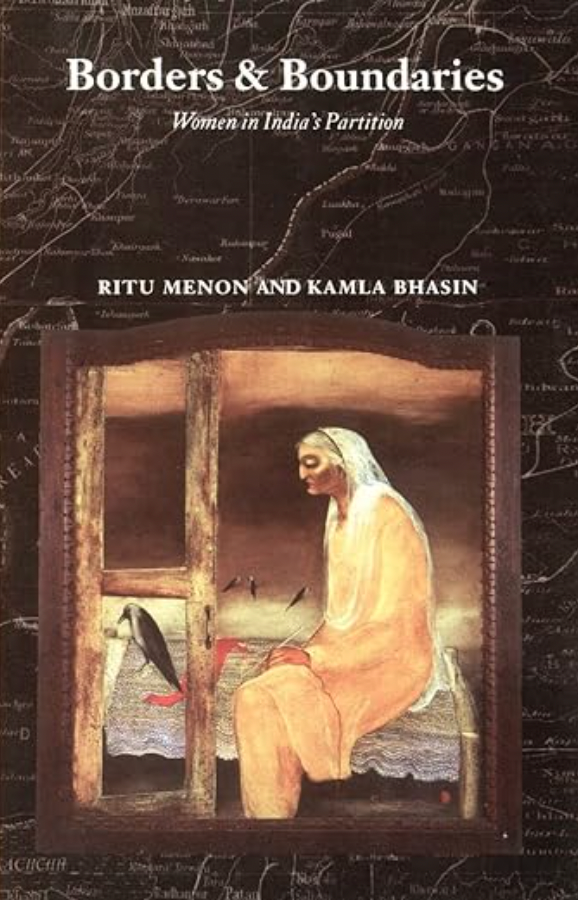

In Attia Hosain’s “After the Storm,” we see how somewomen handled the changes brought upon their lives by Partition. A young girl recounts the violence through a detached, almost fairytale-like lens. She refuses to fill certain gaps in her journey from the refugee camp to her adoption as a domestic servant into the current family. Detachment, or sometimes even staunch silence, is often found among the survivors of Partition. Sometimes it is a deliberate choice in order to mute out the pain associated with those experiences and memories. These were pragmatic choices made soas to forget their immeasurable losses and restart their lives. Such deliberate detachment or silence is oftenfound in the accounts of the interviewees of Aanchal Malhotra, Ritu Menon and Kamla Bhasin. Some of them even asked their interviewers or wondered aloud, “Why rake up the past?” or “What is the use of asking all this now?” The protagonist of Attia Hosain’s story similarly displays reluctance to divulge certain parts of her life story. Yet, not everything is forgotten and she fondly remembers parts of her previous life that now elude her— material comforts, promises, food, flowers.

Literal domestic servitude undergone by women also features in Jamila Hashmi’s “Exile”. Bibi is abducted by a man and brought into his family under the guise of being daughter-in-law to his family. But in reality, she is to serve his mother. She says that in the wilderness of her new house, she is like a “lonely tree which neither blossoms nor bears fruit,” despite bearing children to her abductor-husband. But perhaps she does continue bearing fruit by the way she dreams and imagines fairy lands: entangled roads, fragrances that seem familiar, journeys unending, fears unknown, and the relationships between human beings and the earth. Fictional literature on Partition provides a rich source where often women speak for themselves. “Exile” is one such story where we get a glimpse of how women made sense of their uprootedness by means of dreaming and drawing analogies. In “Exile”, we find the very nuanced and complex thought processes of Bibi who is hurled into circumstances she had never anticipated before and how she tries to cope with them. Caught between hope and hopelessness, over years, Bibi is also given a new name- Lakshmi, and grows undesired roots in her new home. Her dreams of a better life are a stark contrast to her harsh reality.

In Shobha Rao’s “An Unrestored Woman,” Neela’s fate, like that of many other women during Partition, is dictated by the whims of men. The news of her husband’s death in the violence leaves her contemplating a bleak choice: the ascetic life of a Hindu widow, or the degradation she endured in her marriage, where her husband likened her to an animal. She is not free of judgement even in widowhood, and is labelled a “useless item” by a village elder. Her stature is thus decided by the life or death of her husband. The story poignantly illustrates how women’s value was often inextricably linked to their marital status and decided by patriarchal standards. Neela, whether married or not, is assigned a degraded position, unworthy of even being regarded as a human being solely on the basis of her gender. She represents all women who are considered as objects and not subjects, even in historical accounts. This ensures that their words and accounts are not valued and thus they are left behind in history. According to Urvashi Butalia, power and privilege play an important role in determining which stories are preserved and which are forgotten and left behind. Women’s accounts are not considered general or mainstream, rather they constitute a history from below. The testimonies of women are often regarded skeptically, are dismissed or not trusted, and considered to be exaggerated and marred by nostalgia.

In “More Sinned Against Than Sinning” by Umm-E-Ummara, we find that even women loved by their husbands often have to shape their lives according to the latter’s dictates. Amma, though deeply loved and respected by her husband, Baba, faces a heart-wrenching dilemma during Partition. Baba’s decision to relocate the family from Bihar to East Pakistan means leaving behind herbeloved siblings in their ancestral home. Yet ultimately, she has to give in to her husband’s decision. The story also delves into the changing family dynamics that took place due to the family resettlements that happened during the Partition. One of the daughters of the family, Munni, feels lonely and ignored. But as she grows older, she assimilates herself into her new environment and is hopeful that one day the locals will no longer view the migrant settlers as outsiders. According to Krishna Sobti, writers waited for years after the Partition to write about their experiences so as to have a clearer picture of the events without any ideological and mental blinkers. This is reflected in Munni, who feels no animosity towards the locals that view the migrants such as herself as outsiders or “others”. Instead, she hopes for equality and equanimityamong all the people.

In “More Sinned Against Than Sinning” by Umm-E-Ummara, we find that even women loved by their husbands often have to shape their lives according to the latter’s dictates. Amma, though deeply loved and respected by her husband, Baba, faces a heart-wrenching dilemma during Partition. Baba’s decision to relocate the family from Bihar to East Pakistan means leaving behind herbeloved siblings in their ancestral home. Yet ultimately, she has to give in to her husband’s decision. The story also delves into the changing family dynamics that took place due to the family resettlements that happened during the Partition. One of the daughters of the family, Munni, feels lonely and ignored. But as she grows older, she assimilates herself into her new environment and is hopeful that one day the locals will no longer view the migrant settlers as outsiders. According to Krishna Sobti, writers waited for years after the Partition to write about their experiences so as to have a clearer picture of the events without any ideological and mental blinkers. This is reflected in Munni, who feels no animosity towards the locals that view the migrants such as herself as outsiders or “others”. Instead, she hopes for equality and equanimityamong all the people.

Ritu Menon and Kamla Bhasin have called Partition fiction a kind of social history and it seems to be an apt categorization. These fictionalised accounts are representative of the multitude of experiences that women underwent during Partition. The women in these and other stories are survivors and fighters, but also victims of a time not unlike war, where women become symbolic cultural objects to be possessed, humiliated and mutilated. What is remarkable about these stories is that the female protagonists are multidimensional human beings just as women in reality are. They are several things at the same time—hopeful and hopeless, vulnerable and resilient, childlike and adult, sad and happy, brave and scared. They possess conflicting thoughts and feelings. Therefore, their experiences are not homogenous, even though we find a common gendered experience of Partition among them. Although these are fictionalised accounts, they do not seem to be so. Alok Bhalla calls these fictional stories both autobiographical and biographical because their writers based their stories on their own experiences of the Partition, or draw on the experiences of others. Indeed, these stories may even be used to fill in the gaps found in archival reports, memoranda, government documents and official statements or corroborate with these official records.