‘Mulaqat is a time

When women visit men in prison

And no one visits the women in prison…’

Prison remains one of the central metaphors in feminist herstories. Prisons caging our bodies, minds, souls; prisons shackling us within family, within marriage, within gender roles, with norms and ‘morales’ of society; prisons of love, prisons of protection – all equally violent gnawing at our wings, limiting our flight, reigning in our rage, our speech, our imagination. Feminist herstories are about these unfreedoms and the prisons we break. It is about the unwavering hope of razing prisons to the ground. But who writes of those women in prison?

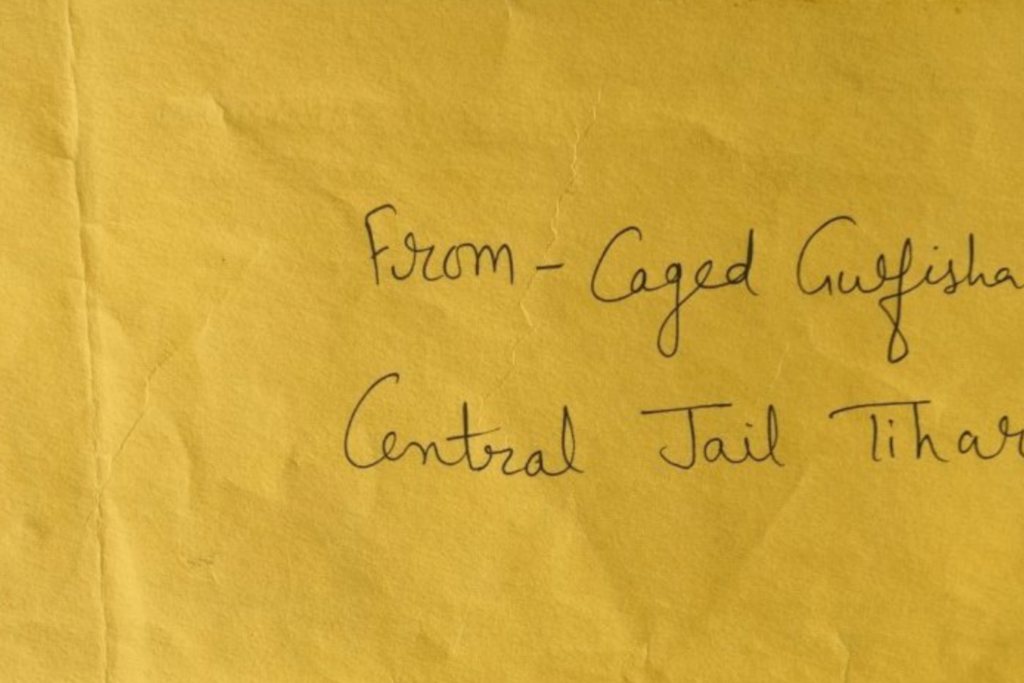

In their letters to friends and comrades from Tihar Jail No. 6, Devangana Kalita and Natasha Talwar, write how women’s lives under patriarchy have always been ‘training for jail’ – of being instructed, of being curtailed, of being limited. Yet, the lives behind the tall walls and towers of prisons can seem too removed, too unfamiliar, too insulated from the secured bubbles of our middle class lives. As the criminal justice system banishes people behind bars, it strips them off everything that makes them ‘them’. The very act of the prison record is to reduce a person to a case number, a name tag, shoving all one was, all that one could be, in a small box shelved ‘off the record’. One is no longer a person, but a prisoner. Unwanted, discarded, as no one wants a criminal on their record. Yet, even in prisons friendships bloom. And it is through these friendships, togetherness, home gets rebuilt.

Feminist histories have mostly been built from the margins – from scraps, scribbled notes, footnotes, erasure, struck out words, discarded crumbled rough sheets, notes on recipe books,, unsent letters, riddles and metaphors. It is an investigative exercise of tracing out words written in invisible ink, and sometimes, seeking out the words women have penned of their lives, of reading into hesitations, pauses, blanks, punctuations. It is this context that Sudha Bharadwaj’s stories from Phansi yard, B Anuradha’s notes from Hazaribagh jail, Devangana- Natasha’s letters from Tihar Jail 6, memoirs of Seema Azad, Anjum Zamarood Habib builds a new archive, a new record of not only women’s political lives, of their struggles against powers that be, but also of the life that bustles in jail.

While their own political journeys are too seditious to be written in print, these accounts talk of friendships, comradeships, solidarities built in prison – forbidden friendships that defy societal laws of who should be befriended, how, and how much. It is through these accounts that we are able to bear witness to the lives of those numerous women (mostly Muslim, adivasi, Dalit women) whose lives are otherwise only recorded through numbers – Case numbers, barrack numbers, number of hours spent waiting for someone to turn up at mulakats, number of years spent waiting for trial, number of cheques needed to be bailed. It is through these stories that we know of the young Muslim sisters who have been charged of kidnapping who draw caged birds being freed calling them ‘jail ke sapne’ (dreams in jail). It is these stories that tell us about Phoolmoni, an adivasi woman who had gone to the jungle to graze her goats but was arrested for stealing goats only to be slapped with charges of being a maoist. It is these stories that acquaint us with the Amma whose parents were killed in a riot in Meerut, who was a Hindu but practices Islam as well.

They speak of the missing women who have been jailed for trafficking, only for crossing borders in search of work. They talk of the women in prison for killing abusive husbands, for loving ‘wrong’, for living ‘wrong’. They bring to light the dreams of children growing up within prison walls – who have never seen the sky, never seen a rainbow. They bring to life vignettes of international working women’s day celebrations in barracks providing them an opportunity to sing, dance, to act – to be Fatima Sheikh or Savitribai Phule. And above all, to be more than just a number, more than an inmate, more than perhaps the life that has been prescribed for them, to be a person again, to laugh, to love, to dream again, within bars, despite the bars.

For women whom society neither allow the time to dream nor the leisure to make friends, being stuck in a limbo of endless waiting, ironically, while stealing time away from their lives, also offers time – time to make friends, to forge solidarities, to share their hopes and dreams, to live holding on to each other, leaning on each other. For most of these women, the stigma of jail also means being abandoned by husbands, families, neighbours, lovers, friends, of being written off office records, family trees, marriage registers. No longer accepted as daughters, wives, daughter-in-laws, aunts, sisters – oftentimes, friendship becomes the only relationship that perhaps survives, and sustains.

In a place designed to humiliate, it is these friendships that become sites of resistance that enable one to survive, to hold on to the humane. Thus, writing about life in prison also becomes an exercise in writing friendships, in keeping records of and remembering friends.. It is an act of resistance against a patriarchal system that criminalizes women’s desires, autonomy, and political agency. Friendships in prison are a refusal to let the criminal justice system dehumanize people. They are also a form of bearing witness to lives that are meant to go unnoticed, that are deliberately invisibilized, and preferably unheard. They shift the conversation instead to women’s resilience, and a tribute to a deep feminist legacy of sisterhood, of comradeship. As B. Anuradha writes of her desire to read Mary Tyler’s diary while sitting under the same tree where she probably wrote it in Hazaribagh jail, as Devangana, Natasha writes of reading Rokeya’s Sultana’s Dream in Tihar jail with the other women, as Sudha writes of Shoma Sen who is still in prison, another history of sisterhood and comradeship gets built – one that transcends generations reminding us of all those whom history chose to forget, all those who dreamt of radical possibilities.

It is in this reading of feminist solidarities, in this refusal to forget, in these myriad ways of weaving seditious stories, that the indomitable hope of breaking prisons is kept alive.

______

References and Sources:

- Haripriya Soibam, ‘In Prison’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oFcl-EioEXc&t=33s

- Imprisoned in 2020, for speaking truth to power against the discriminatory communal citizenship laws slapped on us by a fascist state,

- Devangana Kalita and Natasha Talwar, ‘“Love and Rage”: Natasha and Devangana’s letters of hope and resistance from Tihar Jail 6’, The Caravan, 2021

- Sudha Bharadwaj, From Phansi Yard : My Year with the women of Yerawada, Juggernaut Books, 2023

- B. Anuradha, Prison Notes of a Woman Activist, Ratna Books, Agora Prakashan, 2021

- Seema Azad, Aurat ka Safar, Jail se jail tak, 2021

- Anjum Zamarood Habib, Prisoner No. 100: My Account of my nights and days in an Indian Prison, Zubaan, 2015

- ‘Mulakats’ refers to visiting hours in jail

- Mary Tyler, My Years in an Indian Prison, Penguin, 1977

- Shoma Sen, Sudha Bharadwaj, Jyoti Jagtap and several other activists have been imprisoned in India since 2018 in Bhima Koregaon case for organizing a meeting and being part of anti-fascist resistance in India.