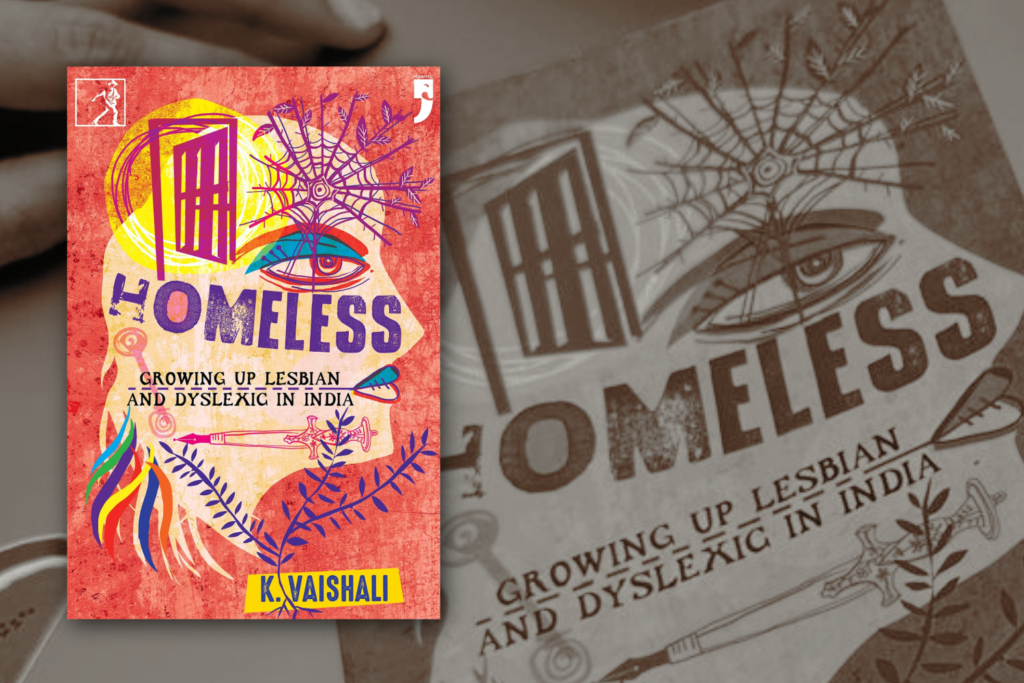

Lovers of book clubs will know that the act of reading together makes for a special sort of alchemy. Last month our in-person book group read K. Vaishali’s memoir ‘Homeless: Growing up Lesbian and Dyslexic in India’ and for the first time, decided to write together as well.

So how do you weave multiple voices and perspectives into one write-up? We decided to share themes from our collective discussion, interspersed with words written by Vijaya, Sangeetha, Sarah, Shahana and Shymala. With the exception of quotes, each writer’s words are mixed in, as it would be in discussion, shared by all. It also helps that we all felt incredibly moved by K. Vaishali’s writing, and life.

A Deeply Honest Reckoning

‘Homeless’ centres on a time in the writer’s life spent at a women’s hostel at the University of Hyderabad, interspersed with memories of a childhood marked by neglect, cruelty and transactional love. She negotiates life as a young, dyslexic lesbian in India, choosing independence of thought, space, values – even when it entails devastating loneliness.

“To read ‘Homeless’ is to reckon with the extent of privilege we take for granted: reading effortlessly, unconditional love from family, a room in a home with a clean toilet, comforting meals.” – Sangeetha Bhaskaran

With incredible honesty and tactful humour she shares experiences of losing a home after coming out to her mother, how she came to test herself for dyslexia and dysgraphia when none of her teachers recognized the signs, and the oppressive constraints placed on women in our society. In the same tone she shares her experiences of finding home, shedding intergenerational trauma, navigating life, dating and love. This is not a linear chronology of events, much like life, it is messy and the highs often live in the same moment as the lows. The thinking that drives her decisions, the trauma etched on her skin and heart, her privilege, her fears, all are bared with no attempt to sanitize or over-explain for the reader’s benefit.

“Homeless has been written with such honesty, it is overwhelming. Reading sections of the book made me feel as though I was navigating through this busy, crowded, noisy street in the midst of a massive downpour, trying pathetically to avoid the muddy back splash.” – Shahana Raza

Where Home Lives

Home, and how we define it, is a common thread stitched across K. Vaishali’s memoir. She begins narrating her story while physically homeless, positioning her decision to study at a public university and stay at a women’s hostel as a way to “live rent-free for two years,” with the degree as a bonus. She recalls the multiple times her family moved cities, schools and houses, and each time needing to make a new home. And of course she speaks of feeling at ‘home’ in one’s body and mind.

“What struck me most was the title. Homeless speaks to the deeper reality that if you do not fit in to acceptable societal norms, finding a place where you feel at home becomes almost impossible.” – Sarah Khan

Her experiences raise the question of what makes a home, and how the homes we live in might be the most toxic and claustrophobic places to exist. She talks about her family’s inability to see her for who she was, not entirely because of their prejudice but for their own dysfunction and inherited intergenerational violence. She writes, “I spent 20 years not knowing that it was okay to be a lesbian and that it was okay to be dyslexic: that it wasn’t my fault for not trying hard enough, it was just the way my brain and body were wired. Instead, I hid my true self, pretended everything was fine, lying about it all because I couldn’t explain who I was.”

“Whether it’s people clinging to rigid norms or a family that refuses to see you for who you are, belonging slips further out of reach. That, to me, was the most devastating; that some of us can feel homeless, within ourselves and out in the world. Forever trying to be at ease, however, always waiting for the other shoe to drop.” – Sarah Khan

Navigating the hostel as her new home is central to the narrative and her reflections are so on point, there is a strong sense of clarity in how she sees herself and the circumstances around her.

“Her powers of observation are simply phenomenal. Having stayed in a hostel myself, I am all but too familiar with those beady eyed large lizards, ‘deemak’ infested woodwork, what passes as food in the mess, those controlling apathetic wardens” – Shahana Raza

She shares anxieties of being ‘found out’ as a lesbian, using unsanitary shared bathrooms, dating strangers and is frank about her own ignorances, caste privilege, and prejudices. Through all this, her finding home in a gendered sense, was a joy to read. She writes:

“I’ve never seen women move so freely; in the few moments I spent in the hostel, I saw a woman braiding her hair, another stepping out of the shower wrapped in a towel, another ringing the prayer bell and chanting a shlok, another eating directly out of a rice cooker, and yet another practising a Bharatanatyam sequence. There was something mesmerising about how free women are when men aren’t around. I’ve never been in a public place without men before. I look forward to not worrying about inviting sexual attention for wearing short shorts or spreading my legs too wide or roaming about in a t-shirt without a bra. This is how being in public should feel like to a woman.” – K. Vaishali

We Need More of This

As readers, we emphasize the value of publishing stories by young people on the margins of the mainstream, and we love that Yoda Press helms a vast canon of queer narratives. Even Vaishali points to the dearth of publishing opportunities or lesbian protagonists with humour and candor,

“I could always make my protagonist a lesbian, but no publisher would risk signing this novel (would they otherwise?).. but I wouldn’t be writing at all if I cared what publishers think.”

“Vaishali heals through writing and tactful humour: calling herself a litmus paper to someone’s experiment in sexuality, equating a square foot of Mumbai to potatoes – everything for sale to the highest bidder, cigarettes as a way to extend her desire to live on. You aren’t supposed to feel sorry for her but question systems and circumstances that make survival such an ordeal.” – Sangeetha Bhaskaran

Although hard to come by, stories that show the intersections of living as a queer woman with dyslexia, dysgraphia, anxieties, a dysfunctional family, in financial instability, looking for love, and making a career, need not be stories of the ‘other.’ These are just as universal.

“From the Gujju family in the train to her take on why bicycle saddles for girls and boys have the same ergonomic design – her critique of class, caste, gender stereotypes in society are particularly praiseworthy” – Shahana Raza

As a group we also wanted more of Vaishali’s story, and were keen to read about her journey to graduating as a gold medalist, and finding joy and love on her own terms.

Writing is Healing Work

The first lines of Homeless are “I read online that writing can be therapeutic. I don’t know about that, but I can’t afford therapy and writing is cheap.” Later she puts it in the context of her dysgraphia “I understand the irony of being a writer with a writing disorder. But I can’t help it. I have thoughts swimming around in my head that keep editing themselves into neat sentences and only leave my head when I write them down.”

Telling your story, as Nawal El-Saadawi says, is “to write yourself into existence.” What makes Homeless so moving is just this. Vaishali’s writing, as she puts it, is necessary for her, and it is necessary for us as readers to feel, through her words, the depth, nuance and desires of a life that refuses to be contained by labels.

.

.

.